6. Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore (1974)

Sometimes critical and/or popular perception, certainly in the cinematic world, can be a tricky thing. In classic Hollywood, George Cukor was often labeled a “woman’s director”, yet, in fact, he directed more male actors to a best actor Oscar than anyone else. By the same token, in modern Hollywood, the much acclaimed Martin Scorsese is considered a “man’s director”.

If one takes Academy recognition as some sort of measure, then that is incorrect, for he has directed about as many female thespians to nominations and awards as male ones. In fact, many forget that the first two of his actors to ever be nominated, with one of them his first winner, were women. This really isn’t so surprising as many also seem to forget that he directed the film which gave these women their showcase (though, admittedly, he did not write it). This was a real outlier in his oeuvre, the feminist classic Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore.

Most films of this type and era usually had a basically strong woman leaving an unworthy man, finding a great career and the type of handsome, wonderful, understanding perfect man who doesn’t often exist in real life. Alice somewhat steps away from that pattern (though the last mentioned element appears surely enough in the form of Kris Kristopherson in the film’s second half).

The story centers on one Alice Hyatt (deserving Oscar winner Ellyn Bursten), who, as a little girl, fancied that she could sing better than Alice Faye. Well that dream went nowhere and, as the film opens, she’s a very likeable but very average housewife, living with rough-hewn and none-too-sensitive truck driver husband Don (Billy Green Bush) and her somewhat bratty, mouthy, little squirt of a son, Tommy (Alfred Lutter), an eternal wise-guy.

A fatal auto accident ends Alice’s drab marriage and stable, if humdrum life, and she must make a new one for herself and her son. She jaw droppingly decides to head for Los Angeles to try for her long dormant idea of a singing career, though with no real prospects (her singing has improved since childhood, but not all that much).

Alice never reaches L.A, though her travels take her across the US southwest and she finds a tough path along the way. After a stint as a lounge singer, tied to a disastrous relationship with a married man, she ends up s a waitress in a tacky, if friendly, diner and learns to see reality more clearly.

The script of this film may not be perfect but its heart is in the right place. Thankfully, writer Robert Getchell was willing to work with director and cast to improve on his original. One huge change was a wonderful scene involving a distraught Alice having a deep conversation with her sassy, down-to-earth co-worker Flo (nominated Diane Ladd), who, as it happens, is making the best of several unhappy situations of her own.

Also appearing in the fine cast are Harvey Keitel (an early Scorsese regular) and a very young Jody Foster, making her first step away from her juvenile career (and the director would help truly give birth to her adult career by casting her in Taxi Driver two years later, giving her a first nomination).

No, there are no tough urban streets in Little Italy or somewhere in New Jersey, no mob guys, no wackings or even much tough talk. However, Alice is good, honest film making and a very touching film in the end (albeit with a good sense of humor), a fine, if unorthodox, addition to its director’s filmography.

7. The Passenger (1975)

For someone as acclaimed at his best as he was and for someone having as long a domestic career as he did, Italian film maker Michelangelo Antonioni’s time in the international spotlight was rather brief. He came to international prominence with 1960’s then controversial, now classic L’Avventura, conquered the English language cinematic world four films later with 1966’s Blow-Up, a big critical and trendy box office hit, then tapped out completely with 1970’s Zabriskie Point (which looks a bit better today).

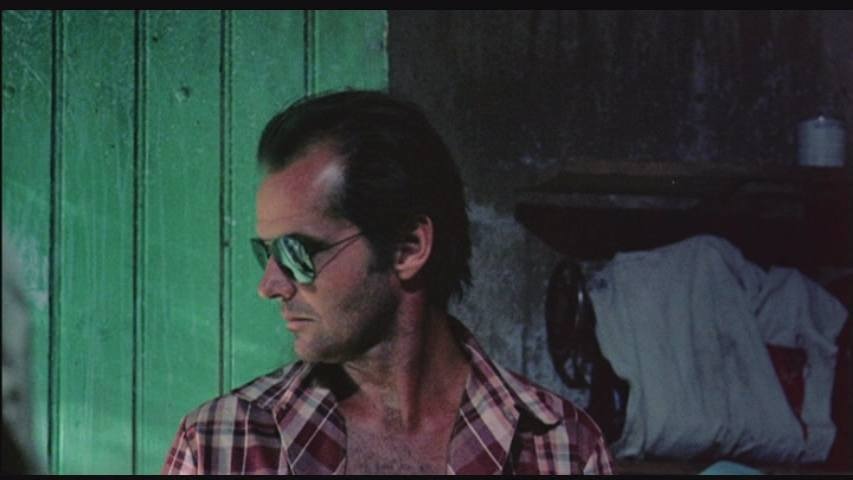

After that one misstep, it seemed like the international doors shut in his face. However, thanks to Hollywood star (and superb actor) Jack Nicholson accepting his offer the film known in the English speaking work as The Passenger was given an international release. While it didn’t score the tremendous reception accorded the film maker’s work of the 1960s, many discerning critics and film fans were happy to see another subtle, sophisticated, deeply thought-out Antonioni film.

Nicholson portrays David Locke, a US born reporter working for a British newspaper. Locke has been sent on a wearying assignment to North Africa and makes the acquaintance of a man with the same general appearance as himself in an out of the way hotel. Shortly after arrival, the other man dies of a heart attack.

Locke makes the mystifying decision to assume the dead man’s identity and give the deceased his own. Now officially dead under his own persona, he decides to keep the appointments listed in the dead man’s journal and discovers that his new identity is that of a gun runner involved in a dangerous situation.

Locke forges ahead into what is, at the very least, a new direction and also comes into the orbit of a lovely but rootless young woman (Maria Schneider, then just coming off 1973’s infamous/acclaimed Last Tango in Paris), another lost soul. Can he really create a new life or he doomed to repeat old patterns in a new place?

Much like Blow-Up, The Passenger is another mystery without a solution. As adverse to exposition as ever, Antonioni gives no real information about Locke’s former life in London or why he was so open to giving up wife, home, and position for the most uncertain of futures.

It might seem quite hollow but for the film maker’s sure artistic touch and the most dedicated of performances from its lead player, then at the height of his career and powers (he would win his first Oscar for One Flew Over the Cukoo’s Nest around the time this film was made).

To this very day, Nicholson lists the making of this film as his best professional experience. Sadly, it didn’t quite have the happy ending it might have. The critical response was mixed to good but the box office was indifferent. Perhaps Antonioni’s moment had simply passed and an increasingly less adventurous cinematic era couldn’t accommodate his work.

Thankfully, time has been kinder (and Nicholson, who owns the negative, had it lovingly cared for and restored over the years). Film historian David Thomson has become an absolute cheerleader for the film in recent years, among others. Maybe its day will come yet.

8. Blood Simple (1984)

First films can be rather dicey in terms of a greater career. Many a film making career has started with a disaster that must be overcome in order for the film maker to continue with his/her career. On the other hand, how many other film makers have made a splash with their first film, only to never scale such heights again. Leave it to the great team of brothers Joel and Ethan Coen to make a debut just good enough, but not too good that it wouldn’t leave room for artistic growth.

Coming out of also nowhere, the brothers independently released what would now be termed a neo-noir thriller made on almost no budget and still had it taken seriously by the film industry (this accomplishment made not seem great in an age when films can be made with phones but it was much more so then).

The brothers could only afford a not very notable TV actor (John Getz) as the male lead, a more noted TV actor as secondary villain (Dan Hedaya), a reliable TV/movie character actor (M. Emmett Walsh), who had never landed that one great role as primary villain , and a leading lady (Frances McDormand) who had only appeared in industrial films up to that point (oh, how that would change!). They had to film on low rent locations in Texas and work with a minimal crew. Yet they made it work!

Blood Simple starts off telling a tale too familiar to film noir fans. The young wife (McDormand) of a pretty revolting small town big-wig (Hedaya) is having an affair with a man (Getz) better suited to her age, comeliness, and temperament. The husband has the pair trailed by a really sleazy old P.I. (Walsh). The detective gets the goods on the pair, who aren’t trying too hard to cover up, easily enough.

The first surprise is that the husband inquires of the detective how much it would cost, not to take the wife and lover to court, but to have the P.I. kill them! The detective agrees to a price but he has a deadly agenda of his own and all involved with end up involved in a deadly circumstance.

It might be nice to say that the Coens and McDormand (now famously long married to one of the brothers) came out full blown but that’s not the case. All concerned show promise here but this is not the best work of any of them. However, for a first film made largely by those lacking professional experience, Blood Simple is remarkably assured.

The script is full of twists and turns and the now usual out-left-field events which makes the film a forerunner of all the clever Coen films to come. While Walsh (in an award winning performance) takes the acting honors (and it came very late in his career), McDormand does show a good deal of professionalism in her feature debut. Though better things (among the best in modern cinema, certainly US cinema) were to follow, Blood Simple got the Coens and company off to a fine start.

9. The Straight Story (1999)

After creating Eraserhead (1977) and Blue Velvet (1986), among other startling films, what could be left for David Lynch to do in order to shock audiences? Well that answer came with the release of The Straight Story: he made a G rated film! (Even for the man who would one day make 2001’s Mullholland Drive and 2006’s Inland Empire, that’s still a shock). The ever greater surprise is that 1.it’s every bit as much a David Lynch film as any in his cannon and 2. that it’s so good.

The Straight Story is based on true events that are almost as surreal as any other film Lynch has made. Alvin Straight (the marvelous stunt man-turned actor Richard Farnsworth) is a polite but feisty senior citizen living in a remote part of the US west. Physically he is not doing that well. He receives news that his long estranged brother (Harry Dean Stanton) has had a stroke. Realizing that the time for petty differences and bitterness must end, he decides to go and see his brother.

The problem is that he is now too physically challenged to drive legally. He ingeniously buys a big John Deare lawn mower and hitches his trailer to it, setting out on a journey several hundred miles long (with the mower going 5mph). The film then becomes picaresque, with Alvin meeting and interacting with an interesting variety of people, taking knocks and scoring triumphs along the way. The film comes to a most moving conclusion.

Lynch used the actual route the real Straight travelled and shot in sequence, noticeably building each episode upon that which came before. He called the film his most experimental. However, all of his virtuosity would have been for very little if the actor at the center hadn’t been extraordinary. That part turned out to be no problem.

Though he didn’t turn to acting until late in his career and life, Farnswoth was always a natural (see his performance in the 1982 indie hit The Grey Fox, among others) and had a presence like none other. He achieves a rare intensity coupled with an enormous innate civility.

This is all the more remarkable in light of the fact that a story every bit as compelling as that in the film was being played out during the making. Farnsworth was suffering from stage four prostate cancer and some wondered if he could even make it through the film. He did and then some, never letting his condition cause problems with the filming, to the admiration of all involved.

The result was many awards and nominations, including one for the Academy Award (his second but first as lead actor) making him the oldest Best Actor nominee ever. Sadly, facing only suffering and pain, he ended his life journey himself shortly after the film’s release. The film stands as a fine tribute to him and is a very good entry in Lynch’s filmography. It might not be as obviously mind-blowing as some other Lynch films, but it’s just as worthy.

10. Broken Embraces (2009)

In 2009 actress Penelope Cruz received her third Oscar nomination, a supporting one for the musical film 9 (she had won in that category two years earlier for Woody Allen’s Vicky Christina Barcelona). The critical consensus was that she was a worthy nominee…but not in that category or for that performance.

That same year saw the release of her fourth film with her longtime champion, the great modern surrealist Spanish director Pedro Almodovar (her first nomination and, to date only one for Best Actress, was for their 2006 collaboration Volver). Though some thought it a comedown from Volver and 1999’s All About My Mother and, while that may be so, second string Almodovar is better than almost anyone else’s efforts.

As usual with an Almodovar film, the plot initially sounds ridiculous but gradually fills with real life due to excellent writing and superb acting from the film maker’s loyal cast. In this case the story starts with a once famous, now blind, screenwriter (Lluis Homar) , writing in braille under an assumed name and living with, and being helped, by his long time aide (Blanca Portillo) and her young son (Tamar Novas).

The plot is set in motion when the man hears of the news that an extremely rich industrial magnate (Jose Luis Gomez) has died. The screenwriter relates to the young man that he had long ago been in love with a beautiful young aspiring actress (Cruz), who, for sadly practical reasons, was also the secretary/mistress to the crude, cruel tycoon.

When the screenwriter, then sighted and also a director, casts her in his newest film, one he and she persuade the millionaire to finance, things come to a dramatic head. This event is followed by passion, betrayal, scheming, jealousy, sabotage, a catastrophic accident, and a change at redemption.

The style, as ever, is reminiscent of Douglas Sirk, the European born Hollywood director of outrageous, wildly artificial, lush, yet deeply felt melodramas of the 1950s. Broken Embraces, like so many Almodovar films, looks like a modern day continuation of those works, only more overtly twistedly ironic.

Almodovar has always been a delight for modern filmgoers of a sympathetic sensibility. Broken Embraces may not be the first of his films to come to most fan’s mind but it deserves a look or two or three.

Author Bio: Woodson Hughes is a long-time librarian and an even longer time student/fan of film, cinema and movies. He has supervised and been publicist for three different film socieities over the years. He is married to the lovely Natalie Holden-Hughes, his eternal inspiration and wife of nearly four years.