7. Madadayo (Akira Kurosawa, 1993)

Based on a collection of posthumously published by Hyakken Uchida, “Madadayo” was Akira Kurosawa’s swan song.

In 1943 Tokyo, Hyakken Uchida, a professor of German studies, decides to retire and to dedicate himself to writing. His students, however, do not forget him, and each year they celebrate his birthday. Furthermore, when he comes into hard times due to World War II, they help him in every way they can.

“Madadayo” is not an epic film as the ones that made Kurosawa one of the most prominent filmmakers of all time. However, man is once more the epicenter, as Uchida proves to be a force that can shape everyone around him for the better. Furthermore, Kurosawa seems to identify with the protagonist, as he shouts “Madadayo” (not yet), since he also was present and shooting films, in spite of his age (83 at the time).

6. Princess Mononoke (Hayao Miyazaki, 1997)

This anime takes place during the Muromachi period in Japan, and begins when a demon from a nearby forest attacks an Emishi village and Prince Ashitaka, the champion of the village, manages to kill him. However, his hand is infected and eventually the villagers discover that the demon was actually a boar god. In order to find a cure and discover the reason behind the god’s metamorphosis, Ashitaka takes a journey into the woods to find the Spirit of the Forest, who may hold his only hope of recovering.

During his travel, he comes across Princess Mononoke, a girl who was adopted by the god of wolves and who was raised among the animals, a fact that resulted in her hatred for humans. Hayao Miyazaki directed an anime that is chiefly characterized for its diversity, due to the large list of characters appearing in it. All of them, however, add to the script and the general aesthetics of the film.

Furthermore, his ecological and humanistic notions are once more evident and elaborately presented, as is the case with his pacifism, since the main characters strive to bring peace among worlds filled with conflict. The drawing and the animation are exquisite as always, and fans of his works will notice the similarities between the main protagonists of this film, with the ones from “Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind”.

5. Ghost in the Shell (Mamoru Oshii, 1995)

Based on the homonymous manga by Masamune Shirow, “Ghost in the Shell” established cyberpunk as one of the main themes of the genre. The anime takes place in 2029, when the world is connected through a vast electronic network that has access to all aspects of life. Motoko Kusanagi is a highly evolved cyborg who works for Public Security Section 9.

Along with her team of experts, she is on the hunt for the “Puppet Master”, a genius hacker whose alleged purpose is to stand against the contemporary oppressive society and its absolute dependence on the aforementioned network.

“Ghost in the Shell” is another anime that chiefly addresses adult audiences, not only due to the graphic depiction of violence and nudity, but also due to its complicated sociopolitical and philosophical context. In that fashion, underneath the techno-action hides an effort to discern the meaning of life through the vast spread of technology, as much as themes of racism and politics in general.

This anime spawned a huge franchise that continues to produce masterpieces. Moreover, it was a trademark of the industry, in both its themes and technological advancement, involving a number of pioneering animation processes.

The scene where a naked Major Kusanagi jumps toward the bottom of a building upside down, and murders her target through the window of the apartment, is one of the trademarks of the industry.

4. After Life (Hirokazu Koreeda, 1998)

Every Monday morning, a group of “advisors” welcomes a number of people who have just died in an institution, in order to help them choose their best memory, the one they want to hold onto forever. On Thursday, a film crew from the same institution starts to produce the chosen memory on film, in order to screen it at the end of the week.

Hirokazu Koreeda directs a film that lingers between reality and fantasy in almost every aspect. Some of these memories are real, from interviews taken when he was working on TV, and some are fictional. The general concept is fictitious, but the way the film crew works and its stress to meet the deadline are quite realistic.

In order to present his message, which is revealed when the reason for the institution and its employees is disclosed, Koreeda has stripped the film from anything unnecessary in cinematic terms, such as special effects. In the process, he has created an utterly pragmatic movie that deals with life and the concept of heaven.

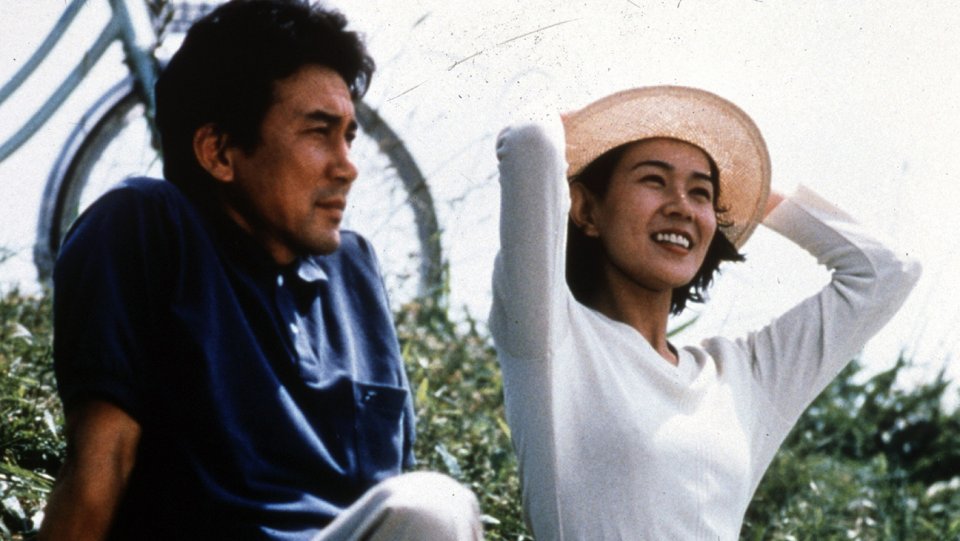

3. Love Letter (Shunji Iwai, 1995)

“Love Letter” was one of the biggest successes of the 90s, becoming a box office hit in Japan, South Korea, and other Asian countries, and finding distribution in the United States.

Hiroko Watanabe still mourns her dead fiancé, who died two years ago on a mountain climbing tour. During a ceremony in his favor, she discovers an old yearbook of his, which also contains his old address. In an utterly illogical notion, she decides to send a letter to this address. Surprisingly, she receives a reply. The exchange of letters continues for some time until Akiba, a friend who has romantic notions for her, decides to investigate.

Shunji Iwai directs a film about grief and nostalgia in the most captivatingly calm and dreamy fashion. Furthermore, he makes a comment regarding memories, stating that sometimes they are shaped by our wishes instead of the truth. Miho Nakayama is sublime in a dual role.

2. The Eel (Shohei Imamura, 1997)

One of the most renowned films of contemporary Japanese cinema, “The Eel” won the Palme d’Or at Cannes, among a plethora of other international and Japanese awards.

Takuro Yamashita is a regular blue-collar worker who likes to fish in his spare time. One day, he receives an anonymous letter, which states that every time he goes fishing, his wife cheats on him. Therefore, he decides to return home early one day. Upon his return, he finds his wife having sex with another man. Almost without remorse, he grabs a knife and stabs them both to death. After this, he surrenders to the police.

Eight years later, he is released on parole along with an eel that he kept in prison as a pet. His parole officer is a priest, who takes him to the village where he lives. Yamashita decides to open a barbershop in that village. Everything seems to be going fine for him, and he even manages to make some friends. However, when he saves Keiko Hattori from committing suicide, his life becomes complicated once more.

Shohei Imamura intends to show the passions lurking underneath the seemingly calm and abiding life of the Japanese people. Furthermore, he shows a number of notions and situations that take place in life, including jealousy, rage, crime and punishment, regret, and guilt. Most of all, however, he wants to present hope and the chance of redemption, from all the aforementioned, through love.

1. Fireworks (Takeshi Kitano, 1997)

Takeshi Kitano plays one of his favorite roles as Nishi, a violent police detective who quits the force due to guilt ensuing from a terrible accident his partner Horibe had, which left him crippled and forced to use a wheelchair for the rest of his life. Nishi tries to help Horibe, who has suicidal tendencies, but at the same time, he has to care for his spouse, who suffers from leukemia.

Nishi, who had to borrow from the Yakuza to pay for his wife’s treatment, has a tough time paying his debt. In an utterly autobiographical component, Horibe tries to fight his sense of despair by taking up painting, the same practice that Kitano used when he was in a similar psychological position. Furthermore, the paintings in the movie are actually Kitano’s own works.

The scenes of the movie unfold in front of the spectator’s eyes, almost like fireworks. Explosions of violence within long periods of joy, flares of paranoia into a sea of lyricism, unforeseen moments of shock perturbing the calm, and all of that tied together with the dreamlike music of Hisaishi, leads to a true masterpiece.

Kitano, who acts in his usual almost catatonic restraint, offers one of the most accomplished performances of his career. His character’s focus is his relationship with his wife. Though he loves her with all his heart, even committing a robbery for her, he never actually shows her his feelings, apart from the finale that truly dismantles Nishi emotionally, letting the audience finally perceive the drive behind his actions.

“Fireworks” is Kitano’s most critically acclaimed work, netting him the Golden Lion at the prestigious Venice Film Festival, and a plethora of other awards, both in Japan and all around the world. However, the Japanese Academy chose to ignore him again, despite 11 nominations, solely awarding Joe Hisaishi for Best Musical Score.

The international success of both “Fireworks” and “Sonatine” established Kitano as the most prominent Japanese filmmaker of his era, thus resulting in the end of his awful psychological condition that had been ongoing for years, even before shooting the latter.

Author Bio: Panos Kotzathanasis is a film critic who focuses on the cinema of East Asia. He enjoys films from all genres, although he is a big fan of exploitation. You can follow him on Facebook or Twitter.