7. No End (1985)

Arguably Kieslowski’s first true masterpiece, No End remains a compelling story told by a director who had finally mastered his craft. His attention to detail remains unsurpassed in Polish cinema, and many of Kieslowski’s trademark themes can be traced back to No End.

No End tells the story of Ulla (Grażyna Szapołowska), a famous translator, who is having trouble coping with the unexpected death of her attorney husband, learns that she must move on and return to society, but doing so appears more difficult than imagined as the spirit of her late husband revisit her in more ways than one.

No End represents the first collaboration of Kieslowski, composer Zbigniew Preisner, and former lawyer now scriptwriter Krzysztof Piesiewicz. The trio would prove to be inseparable as they would go on to collaborate on every film Kieslowski would go on to make. Nevertheless, No End should still be able to be regarded by its merits alone, as it’s still a mesmerizing piece of brilliant filmmaking and belongs together with Kieslowski’s best work.

6. A Short Film About Love (1988)

Regarding the following six films, a case could be made that any of these films could be placed at number one, perhaps a case could even be made for the No End and Blind Chance, Kieslowski is just that brilliant.

The story follows the nineteen-year-old Tomek (Olaf Lubaszenko), raised in an orphanage. He is currently living with his godmother while her own son is away. Tomek could easily be described as a loner; he has few, if any, friends, he is very shy and dislikes chatting with his co-workers at the postal office. He spends most of his spare time spying on a beautiful older woman who lives in the apartment complex opposite to Jacek. He watches her through a telescope as she undresses, but whenever she has sexual intercourse, he always looks away – he seems to be more lonely than perverse.

To get closer to this woman, he calls her but is too shy to say anything. To get even closer to her, Jacek, one day, decides to drop a fake postal notice in her mailbox, persuading her to pick up at the postal office, what she believes to be an unexpected money order.

A Short Story About Love, much like Rear Window, is ultimately about voyeurism, and in many respects, it can be seen as a metaphor for watching movies, however, it would be doing the film a disservice to regard it only as a metaphor. In the film, Kieslowski is able to convey a deep emotional truth about love, a truth that may not mean the same to everyone but will impact everyone who is willing to listen to it.

5. A Short Film About Killing (1988)

One thing is to make a political film – that’s easy. Another thing is to make an appealing political film without turning it into propaganda. That’s what Kieslowski manages to do in A Short Film About Killing. Not only does he make a non-propaganda political film, but he also manages to make a convincing argument against capital punishment, which was still legal in Poland. The fact that the last act of capital punishment in Poland was performed the same year as the release of the film, stands as a testament to the excellence of this film.

The film follows Jacek (Miroslaw Baka) who aimlessly wanders the streets of Warsaw as he displays what seems to be sadistic behavior; throwing a stranger into the urinals of a public toilet; pushing a large stone from a bridge on to a passing vehicle.

The film also follows two other characters simultaneously, at first, it appears as if their stories have no connection to the story of Jacek. One of the stories concerns a young idealistic lawyer who will later come to represent Jacek at the trial. The other concerns Waldemar (Jan Tesarz), a middle-aged taxicab driver who, like Jacek, doesn’t appear very sympathetic; he is arrogant to customers and spends most of his time staring at young women.

One-third into the film the audience begins to suspect, perhaps due to the title of the film, that Jacek might be preparing a murder as he sits at a café while fiddling with a piece of rope, tying the rope tightly around his fists as he later does in the infamous killing scene – a scene which has been hailed as being one of the most gruesome killing scenes in European cinema. While Jacek still is at the café, the scene is intercut with images of the executioner preparing the death chamber for Jacek’s execution – two scenes showing someone preparing an act of murder.

This duality is present again in the ending of the film as Kieslowski goes to great lengths to display the gruesomeness of the killing of Jacek, just as he went to great lengths to show us Jacek’s horrifying killing of the unsympathetic, yet innocent, cab driver. Kieslowski utilizes this duality to force us to compare both murders and decide if capital punishment is any different from cold blooded murder.

Kieslowski’s bleak view of the brutality of the Polish judicial system becomes manifested in the cinematography, most noticeable is the prominent use of color filters which creates a raw, undesirable image. Along with the hand-held camera which offers the film an added gritty feel, Kieslowski greatly enhances the bleak view of the film, thus providing his audience with one of the most shocking political masterpieces of European cinema.

4. Three Colors: Red (1994)

As well as being the final installment of Kieslowski’s masterful trilogy, it also happens to be the final film of his career.

Red examines fraternity within the French Revolutionary ideals in modern France as we follow a variety of characters as their seemingly separate lives gradually become closely interconnected, especially one pair of characters seem to dominate the film.

As Valentine (Irene Jacob), a university student and model, accidentally hits a dog with her car, she tracks down the owner, Joseph Kern (Jean-Louis Trintignant), a bitter retired judge who spends his time spying on his neighbors, using wiretaps to monitor their telephone calls.

Though they have nothing in common they slowly form a meaningful friendship and Valentine helps Joseph reform as he renounces spying on others and rejoins society and begins to show interest in normal human interactions.

A parallel story unfolds simultaneously with the one of Valentine and Joseph. It concerns a young judge, Auguste, who, like Joseph, learns that his wife has been cheating on him, obviously paralleling events from Joseph’s life.

Coincidences seem to dominate the film, which is evident as all the major characters from the trilogy meet at the end of the film through a coincidence. Kieslowski’s depiction of fraternity has been described as being a “metaphysical concept”, which seems accurate as the relationship between the two main characters occurs due to an unforeseen force of nature.

In Red, Kieslowski delivers a powerful examination of the impact of uncontrollable forces in our daily lives – something that most people can relate to. Since the release of the film, Red remains one of Kieslowski’s most accessible and celebrated pieces of works and it resulted in his only Academy Award nomination.

3. The Double Life of Veronique (1991)

The Double Life of Veronique is amongst Kieslowski’s most visually stunning works, but it’s also spiritually challenging as it makes us think, not only about the film but existence itself.

The film is entirely cut into two halves, yet both halves remain inseparable from each other. In Poland, we follow the life of Weronika (Irene Jacob), a joyful girl and a terrific choir singer. Her happiness can be seen as a contrast to the bleak depiction of the city she lives in. One seemingly ordinary day, a musical director asks Weronika to audition, after having heard her beautiful high soprano voice. She wins the audition and suddenly her life is changed.

Her life seems meaningful now. She beings to dream and think of her future. And then, in an unexpected turn of events, at the night of the recital, Weronika suddenly collapses while singing, the musical directors rushes to her body and confirms that she has passed away. In a breathtaking tracking shot, Kieslowski shows us her soul traveling above the heads of the audience.

The story then switches focus to that of the life of a French music teacher, Veronique, who is also played by Irene Jacob. Like Weronika, she is also joyous and dreams of her future, however, Veronique doesn’t seem spiritually restraint by her city. France is portrayed warm and bright just like her personality.

The two women in the film don’t know of each other but they have a feeling that there is something that they are missing. The film suggests that they are spiritually bound together, they seem to be each other’s mirror image but are by no means, two identical persons. And as the film ends with Veronique, like Weronika, having gone through a life-changing event, Veronique still remains alive, unlike Weronika.

The film binds the two stories together by the use of music, especially one piece of music keeps occurring throughout the film, a haunting score composed by the fictitious eighteenth-century composer, Van den Budenmayer. The central use of music is later developed in Kieslowski’s Blue and the music of Budenmayer is even heard in Red, suggesting that his films exist in the same universe.

In The Double Life of Veronique, Kieslowski effortlessly manages to display a social critique of his native Poland without having to elaborate much on it or take the focus away from the core of the story. He does this as he presents us with two similar women, living in two separate places, and as one of them mysteriously dies, it seems likely that she has become a victim of her own environment.

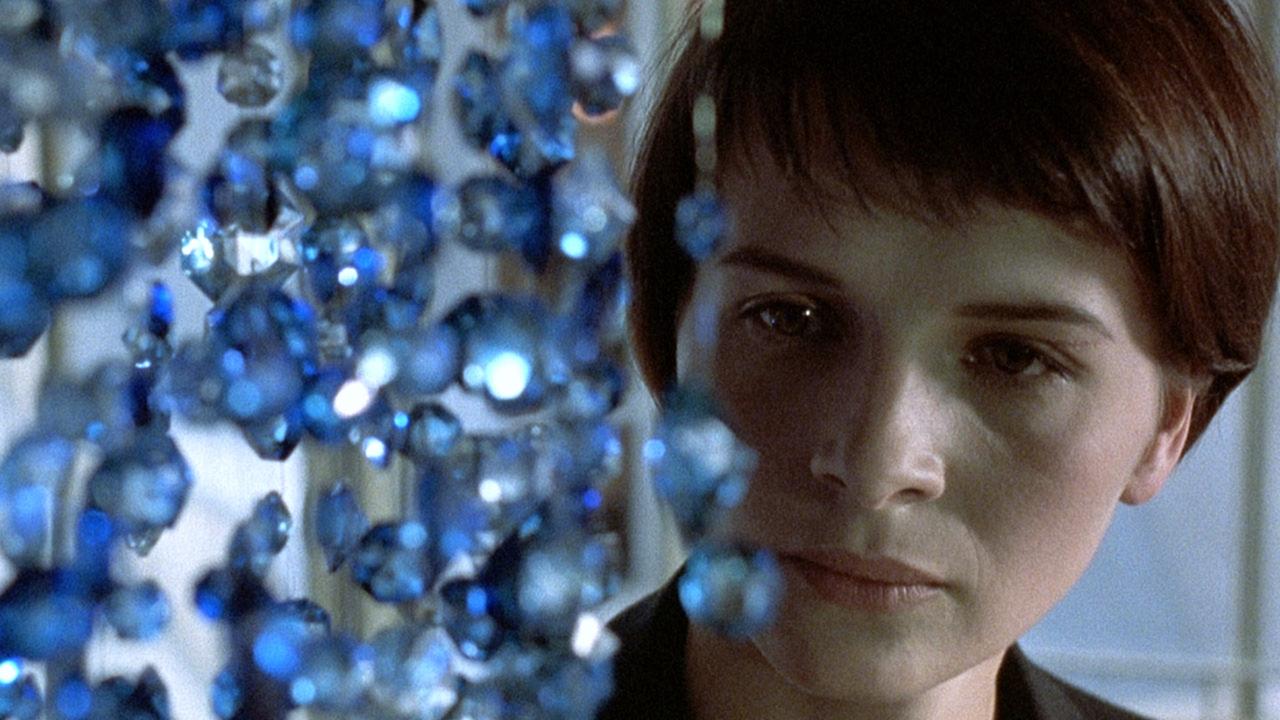

2. Three Colors: Blue (1993)

In 1993, Kieslowski began his epic Three Colors Trilogy with Blue, a film that explores the consequence of complete liberation. To this day, Blue remains one of the most touching stories, illustrating the symbolical journey of loss; grief, then sorrow and finally, forgiveness and the hope of a new beginning.

On top of that, Blue is also one of the most visually beautiful films, not just amongst Kieslowski’s other work, but in the history of cinema. The awe-inspiring visuals of the film are only enhanced by the constant focus on blue colors throughout the film, complimented by the use of blue lights and filters. The genius of Kieslowski is the fact that he utilizes the colors as a way of commenting on the story, thus providing his audience with visual clues to the themes of the film.

This emotional journey is shown through the life of Julie (Juliette Binoche), an acclaimed composer’s wife, who loses her husband and her only child in a fatal car crash, she, being the only survivor. While recovering from the accident, Julie attempts to commit suicide by overdosing on sedatives, but she can’t swallow the .

As Julie tries to move on, she realizes that she must liberate herself from her past by abandoning her physical belongings, her friends, and even her family. In one of the film’s central scenes, she even destroys her late husband’s unfinished score, supposedly a masterpiece. This scene resonates throughout the rest of the film as we, at vital moments in the film, hear small chunks of the score.

At the center of the film is Juliette Binoche, in perhaps her finest performances. Her triumph lies in how much she conveys without doing anything. We can feel her think, reflect, grief, without her having to open her mouth or shedding a single tear, and Kieslowski knows this. This is why he refused to make the movie without her. Kieslowski simply uses all his cinematic power to support her performance and vice versa.

To this day Blue remains one of the greatest film, featured in one the greatest film trilogies, directed by one of the greatest film directors.

1. The Decalogue (1988, TV Miniseries)

The Decalogue is the epitome of a Kieslowski film and much more; every central theme present in Kieslowski’s later work can be traced back to Decalogue. Not only did the series gain a great deal of critical acclaim by notable figures such as Stanley Kubrick and Roger Ebert but it cemented Krzysztof Kieslowski’s name in cinema history. If Kieslowski had retired after finishing his work on Decalogue, he would still be considered one of the greatest filmmakers of all time.

The premise of Decalogue is simple yet the stories are complex; ten different stories, all inspired by the Ten Commandments. Each story follows a different set of characters, who all live in the same high-rise Warsaw apartment complex, and they all face difficult moral or ethical dilemmas.

In these ten episodes, Kieslowski manages to explore the human condition by reflecting upon the different ways the ten commandments are being broken every day in contemporary Eastern Europe, as he studies the consequences, if any, that follow amoral behavior in a society where God becomes less and less prominent in the daily life. But these films are not just that, they are expertly written and shot stories about real people with real-life ethical challenges.

Kieslowski wrote the entire Decalogue in little over a year. He wanted every episode to have a different aesthetic look so he chose to hire a different cinematographer for every episode. This provides the series with some stunning cinematography that never becomes repetitious while it also succeeds in reflecting several aspects of each commandment.

Finally, the magnificent performances of almost all the actors in the series display exactly why Kieslowski is not only a great storyteller but an actor’s director as well. The audience doesn’t need to hear the actors proclaim their inner conflict, they can see it happening just by observing their facial gestures.

The series was immediately hailed internationally as Kieslowski’s definitive chef-d’oeuvre – as it still is to this day – and it allowed him to continue contributing to cinema history even though the film funds in Poland were rapidly running out due to the eventual downfall of the Iron Curtain. This leaves Decalogue as the cornerstone of Kieslowski’s brilliant filmmaking career and as an unsurpassable tour de force in emotional storytelling.

Author Bio: Jonas Skov Pedersen is a Danish student and a passionate lover of film and if he isn’t watching or writing about cinema, he can most likely be found reading Russian literature from the nineteenth century or listening to the tunes of Bob Dylan. A list of his favorite films with detailed critical reviews can be found on IMDb (http://www.imdb.com/list/ls031367581/). He also writes articles and film reviews regularly, in Danish, for Alice (http://alicemag.dk/author/jonass/).