7. Paths of Glory (1957)

A heartbreaking tale of man’s inhumanity to man, Paths Of Glory is the closest Kubrick ever gets to a real tearjerker. Its strength comes from its central moral dilemma: when a commanding officer (Kirk Douglas) refuses to send his men towards certain death, he is then court-martialled for disobedience.

Kubrick’s austerity works wonders here; reflecting the unbending nature of unthinking bureaucracy and patriotism. This is made all the more effective considering the nature of what we have seen before: the utter horrors of the battlefield.

Kubrick makes use of incredible camera-tracking here, moving through the trenches and then onto the battlefield, creating the type of action sequence that was rarely seen before in Hollywood; creating a template that would later be seen in such films as Saving Private Ryan, The Big Red One and the standout sequence in Atonement.

By making these shots run on for much longer than audiences typically expect, Kubrick shows the lingering effects of such conditions on the moral psyche; there is no running away from them, not in a war like this. This is seen in the film’s extraordinarily bleak conclusion, in which Hollywood tradition is done away with, and we are left with the true horror of inhumanity. It still remains an emotional rollercoaster to this day.

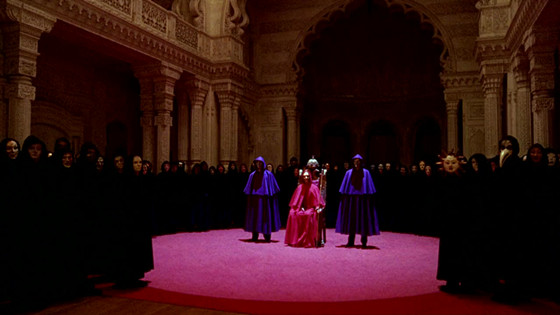

6. Eyes Wide Shut (1999)

Coming 12 whole years after Full Metal Jacket, hopes were riding high for what was Kubrick’s last ever movie, which cast the two biggest movie stars — Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman — of the day. Many were left disappointed — by the three hour run time, the papier-mâché New York (built in London) and the bizarre sexual titillation.

Yet, in this film a different type of Kubrick was emerging, one far more obsessed with the erotic than ever before. Adapting Traumnovelle by Arthur Schnitzler, Eyes Wide Shut is arguably Kubrick’s most grounded movie, as it is based in the very real psychological problems that can occur in a big city between an egotistical man and his wife.

The film tells a story of marital woe, and the late night of the soul some men have when they figure out their wives have sexual fantasies about other men. Perhaps much of the ridicule the film received was that it took female desire seriously, and was willing to satirise the nature of man when he attempts to go deeper into the realm of the erotic.

This is then dressed up in a conspiracy that seems to have no real end; much like a waking dream where you can feel that you are an agent in the story, but unable to achieve any kind of real outcome. Kubrick’s underrated late masterpiece.

5. The Killing (1956)

A film that would change the course of noir and heist films forever, The Killing’s legacy can be seen in films by directors as diverse as Sam Peckinpah, Martin Scorsese, David Mamet and Quentin Tarantino, especially in Reservoir Dogs.

The auteur’s first studio film, it saw him retain his unique spirit throughout nearly ever aspect of the production. The genius of the film is in its constant narrative twists and turns, deploying a breathless and remote voiceover (six years before Jules et Jim) to keep the plot moving at a brisk and highly entertaining pace.

It shows that having a small budget is no constraint for the imagination, Kubrick milking every dollar of its $320,000 price tag in order to squeeze out a taut story of deception and intrigue.

The characters do not know the whole picture, and neither do we; only Kubrick seemingly has omniscience to the events of the heist. He made use of real locations, including sleazy motels and broken-down apartments, to give the film a naturalistic vibe that only heightens this sense of confusion in the midst of a bigger plan.

That the film remains so compelling despite the fact that the plot is almost impossible to fully understand, only shows the mastery at work and the inherent strength of the writing and editing.

4. Dr Strangelove, Or How I Learned To Stop Worrying And Love The Bomb (1964)

Dr Strangelove is Stanley Kubrick’s most anarchic movie, and as a result, his most fun. Revolutionary in its own time for making fun of the cold war and the presence of imminent destruction, it still feels fresh even today.

Its biggest masterstroke was casting Peter Sellers, who gives a career best performance as not one but three different characters. Remarkably for a studio-mandated movie — Kubrick was against the casting — it seems like a move that was planned all along, showing that not every great part of Kubrick’s oeuvre was necessarily controlled by him.

Stuffed full of quotable lines, such as “Gentlemen, you can’t fight in here. This is the war room,” Dr Strangelove is a continuous barrel of laughs. Yet underneath the satire is a serious message about the gung-ho nature of both the Americans and the Russians that could easily have led to total annihilation.

After all, the Russians really did own a Doomsday machine, and there was really nothing stopping a rogue general from launching nuclear weapons. Considering who is now in the White House, its depiction of nuclear warfare started by a madman seems all the more prescient today.

3. Barry Lyndon (1975)

Oft-criticised for being too long or just a little too boring, Barry Lyndon in in fact Kubrick’s most beautifully composed film. Using special lenses from NASA that were hitherto used to photograph the far side of the moon, Kubrick deployed them in order to shoot his nighttime scenes by candlelight.

Here, he mastered the use of the reverse shot; starting from a close-up before backing up to reveal an entire canvas, marking the closest live-action cinema has ever come to resembling the art of painting. The film took 300 days to make, and it shows in the final product; the art direction, costume design and meticulous production accumulating the kind of detail usually reserved for a 19th century novel.

Telling the picaresque story of Redmond Barry, expertly played by Ryan O’Neal as a man to whom things happen, rather than the agent of his own destiny, as he moves through a continent embroiled in war, this reserved yet highly stylised technique of filming is the perfect reflection of his calm worldview.

This is the film that most Kubrick critics would argue is the height of his cold style, yet it is perhaps the most representative film of the notion that technique can guide one’s attitude towards a movie.

2. The Shining (1980)

The combination of Jack Nicholson and Stanley Kubrick in The Shining is one of the finest collaborations in film, turning a very good Stephen King novel into one of cinema’s most riveting horrors. Nicholson gives his second best performance here (after Five Easy Pieces), his peculiar mannerisms turning the character of Jack Torrance into a true yet always compelling enigma.

What Kubrick achieved so well in this film was creating an uncanny mood which although undecipherable still works as pure cinematic experience. From the tracking shots of Danny on his bike, to the two twins in the hallway, to the woman in the bathtub, Kubrick knew that true horror wasn’t merely about jump-scares or a murderous killer, but a lingering sense of dread that keeps on compounding scene after scene.

What makes the film so satisfying is the amount of different meanings that can be applied to it. Whether you think its Kubrick’s apology for filming the space landings, an indictment of American genocide or merely an alcohol soaked nightmare — whatever you feel about the movie can probably be brought to it as a possible interpretation.

However, much like Last Year In Marienbad, which The Shining apes in its suggestion that Jack has been to this hotel before, there is no fixed meaning to the film; making it an experience one can dive into over and over again.

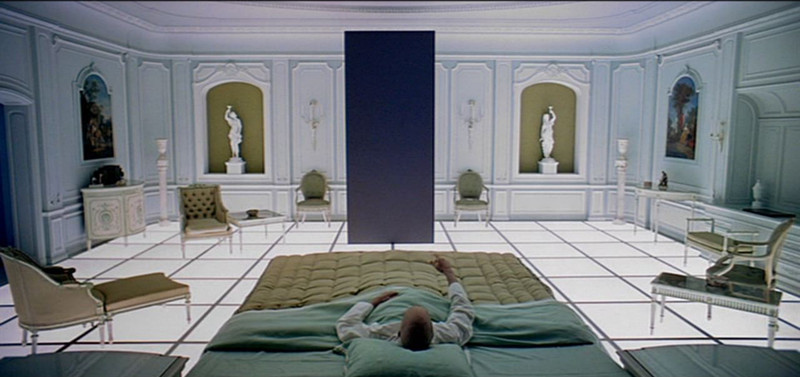

1. 2001: A Space Odyssey (1967)

2001: A Space Odyssey is not only Stanley Kubrick’s greatest film, but surely a contender for one of the greatest films ever made. It is a space epic that takes us on a remarkable journey from the dawn of man to outside the space-time continuum itself.

If any film ever needed to be seen in a cinema, it would be this one. The opening — scored to “Thus Spake Zarathustra” — is as iconic as they come, whilst the ending, in all its enigmatic glory, shows Kubrick to be the most visionary director of his generation, all the more extraordinary for making the film in the midst of the groundbreaking 1960s.

Rarely in the history of cinema has philosophy and spectacle ever complimented each other so well. Whilst the classically-scored sequences of spaceships dancing through space beguile us; the question of man’s place in the universe and the idea of machines gaining consciousness are also pondered to unsettling effect.

What makes the film so successful is that the characters, with the exception of HAL, are never allowed to dominate the screen, ironically making its humanity shine through as a result of its austere yet playful style. A one of a kind experience that still hasn’t been matched.

Author Bio: Redmond Bacon is a professional film writer and amateur musician from London. Currently based in Berlin (Brexit), most of his waking hours are spent around either watching, discussing, or thinking about movies. Sometimes he reads a book.