16. Candy Mountain (1988). Dir. by Rudy Wurlitzer (and Robert Frank).

Ok, ANY film made by the descendant of the inventor of jukebox and that boasts Tom Waits, Dr. John, Leon Redbone, Joe Strummer, and Arto Lindsay in its cast deserves to be seen at least once.

Rudy Wurlitzer is more known as a cult writer extraordinaire, both as a novelist and screenwriter. His novels-Nog, Quake, Flats, etc.-are the definition of trippy, and he wrote scripts for such cult films as Two-Lane Blacktop, Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, Alex Cox’s Walker, Carrol Lombard’s Wind, and Bertolucci’s Last Buddha.

With the help of the director of shorts and documentaries Robert Frank (who achieved notoriety with the Stones doc Cocksucker Blues), he makes a quirky and low-key road movie of a mediocre musician’s quest to find a nearly-mythic guitar making.

If you like the minimalist gems of Jim Jarmusch and Aki Kaurismaki, you’ll love this one (in fact, Jarmusch makes a cameo appearance here). Much like their films, in this one the devil’s in the details, straight-faced surrealism of the scenes, and the overall atmosphere.

And it definitely muses on several important questions-the road itself as metaphor for seeking, the nature of fame, self-actualization. The characters you’ll encounter are seldom pleasant, and usually very much of the pretentious and self-righteous dick sort, but the film never takes itself too seriously, focusing, instead, on the journey rather than destination. Happy trails.

15. The Honeymoon Killers (1969). Dir. by Leonard Kastle.

An unpolished, grimy, and pitch-dark crime film that had a tumultuous production history and was definitely way ahead of its time. The real-life story of late 1940’s serial killing couple has been brought on screen several times (Deep Crimson, 2006 Lonely Hearts), but this film remains the most influential and accomplished of all adaptations.

It’s a miracle that it was even made-the initial director, one Mr. Martin Scorsese, was fired by the producers for being too slow and experimental, as was his replacement, an obscure industrial filmmaker Donald Volkman.

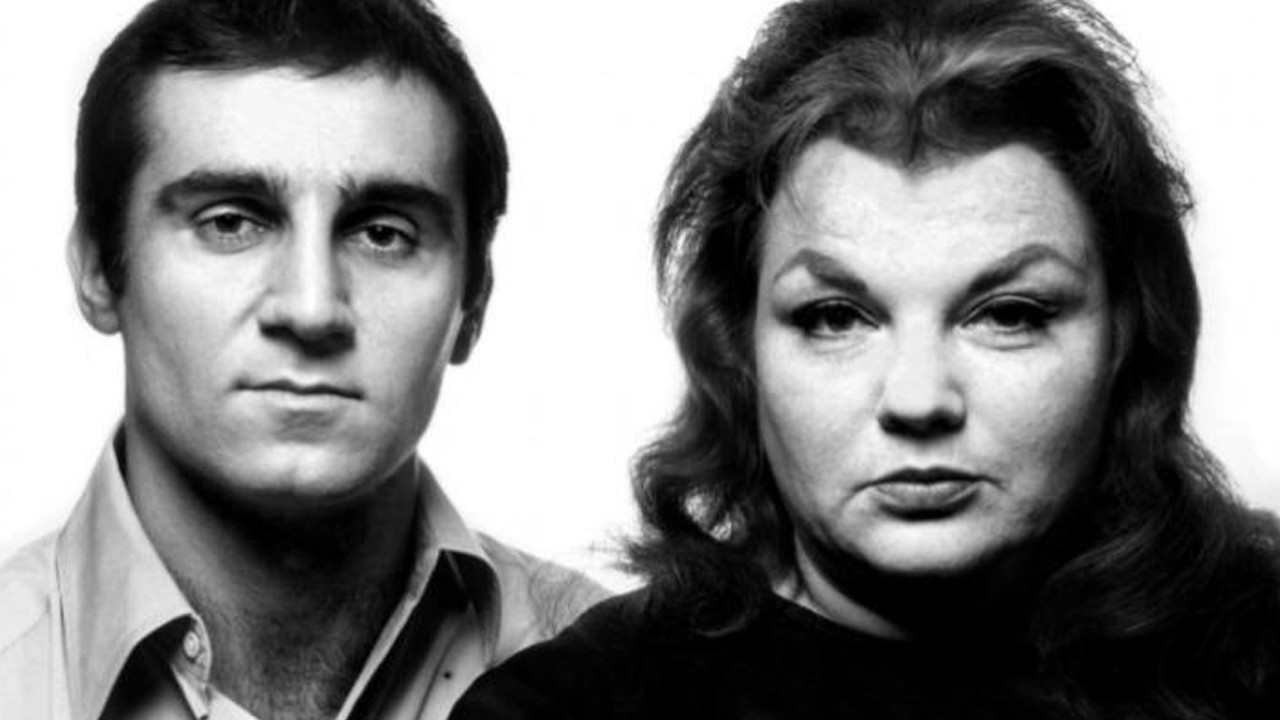

The directing duties thus fell to the screenwriter, Leonard Kastle. Using quality stage actors, Shirley Stoler and Tony Lo Bianco, Kastle skillfully tells the story of a surly, jealous, and overweight nurse who is scammed by a gigolo con artist, but manages to find him and begin a definition of a dysfunctional relationship, in the course of which they murder several women he was working on conning.

This isn’t Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde-these lovebirds are extremely unpleasant people. Who, weirdly, just happen to love each other very much, carrying their love to their electric-chair-induced graves.

Aided by another rookie, cinematographer Oliver Wood (who would go on to a long and distinguished career in both UK and Hollywood, shooting the likes of Face/Off and the Bourne trilogy), Kastle gives the proceedings a “newspaper look”, mostly filming with available natural light only.

This technique was at the time very New-York, to differentiate from the glossy Hollywood photography. Mysteriously, Kastle has completely dropped from the filmmaking world, prompting many speculations. The truth is simple-a composer by education, he simply returned to his day job, eventually teaching composition and music history at the New York State University at Albany.

14. The Outskirts (1998). Dir. by Pyotr Lutsik.

Eisenstein meets Tarantino (with much help from Boris Barnet and George A. Romero). An expertly and uniquely made, darkly funny, visually stunning, and overall amazing film. Lutsik tells the story of oppressed Russian peasants from a remote region who are about to be pushed from their lands. They decide that enough is enough, and begin their senseless, violent, triumphant march upon Moscow.

End result-many officials are grotesquely killed, Kremlin is left burning, while the singing peasants return to their bucolic lives. Lutsik managed to make a highly original film that is ultra-post-modern in the way it employs the 20’s-30’s visual aesthetics of Eisenstein, Pudovkin, and Barnet, while freely adding extreme violence and dark humor.

Every shot is masterful, every monochrome sequence is memorable. And the deeper meaning of Russians being perennially exploited by powers that be is aptly demonstrated. Lutsik began his cinematic career as a screenwriter, where he achieved limited success-often, his scripts would be given a less than adequate treatment by the directors.

So, he thankfully decided to direct himself, with bloody and hilarious results. Unfortunately, he tragically died from a heart attack in 2000, at the age of only 41, thus robbing the Russian cinema of a talented and original new voice. RIP, Pyotr.

13. Die Verlorene (1951). Dir. by Peter Lorre.

It’s a given that Peter Lorre knows a thing or two about psychological thrillers. Since starring in Fritz Lang’s legendary M, he also worked with Hitchcock, von Sternberg, and other legendary directors in the genre. Along with Conrad Veidt, he was the visual embodiment of psychopathy. It’s natural, therefore, that the only film he directed is an atmospheric crime drama.

Made in 1951, soon after Lorre returned to Germany, it tells a story of a Nazi scientist who murders both his fiancée and her doppelganger, and then switches identities, ultimately being driven to a breaking point. Lorre shows that he knows his German Expressionism very well, utilizing its style and telling the story in a series of intense flashbacks.

The fact that the style itself was considered somewhat dated in Europe at the time, not yet enjoying a revival via film noirs, is an explanation for a lukewarm public reception. It may be that the European audiences of the time were simply too war-weary to enjoy more dark and sinuous material.

But, much like noirs and German Expressionist films, it has dated well, and remains very watchable. Lorre proves himself an astute student of Lang and Hitchcock, conjuring up a convincing portrayal of evil (the fact that he played the leading part and was able to transpose his previous film visage onto the role probably helped him considerably).

12. The War Zone (1999). Dir. by Tim Roth.

Imagine sitting in a comfy, well-used Lazyboy chair. It’s not pretty, but is comfortable, and you’re used to it, down to the butt groove and the taped armrests. Then a tiny hole catches your attention. You begin picking at it, slowly revealing years of decay and rot beneath the cover. As the cover comes off, more and more nasty dirt becomes visible, leaving you horrified-how could I have spent so much time in this filth?

Such is the feeling Tim Roth’s only directorial effort gives. On the surface, he presents a typical middle-class family, maybe a bit schmucky at times, but fairly ordinary-Dad, Mum, two teenage siblings, and a baby on the way. They are shown moving from London to a very rainy Devon. But then the 15-year old son begins discovering just how insidiously rotten things are in his family. To his credit, he actively resists this newfound evil, ultimately taking up arms against it.

This is not a comfortable film. Roth pulls no punches, and the abuse is shown in all its horror. Made a year after Vinterberg’s celebrated “Festen”, it shows similar themes. Life in an abusive family is much like life in the war zone, where your very surroundings can go from calm to chaotic in an instant.

Here, the downward spiral is shown well, with everything turning ugly towards the end, and the lyrical, rain-drenched meadows of Devon used as a very ironic backdrop.

Roth directs the young actors well here (one of the supporting characters is played by a very young Colin Farrell), and he also gets great turns from the talented Ray Winstone and Tilda Swinton as Dad and Mum. The film enjoyed good reviews, and yet it’s not a given that Roth will ever direct another film again.

11. Dementia (a.k.a. Daughter of Horror) (1953, rel. 1955). Dir. by John Parker.

Known for a long time as “that B-movie that plays in the movie theatre sequence of The Blob”, this utterly strange and mesmerizing cult classic was, fortunately, rediscovered and recognized for what it is-a compelling and fascinating film. Part avant-garde, part noir, part B-horror, it utilizes the stylistics of German Expressionism, mixing plot elements with pure flights of the dark imagination.

It’s all here-weird sets, complete or partial lack of lighting, strange shooting angles, weird sounds. Add to it that the theme here is the immersion into the depths of human sub conscience-and you have yourself a dark and scary cinematic ride. The experimental element is the complete dispersion with dialogue-just the incidental noises and the eerie score by a famous avant-garde composer George Antheil. Watch it in the dark, and prepare to be shocked.

The main question remained for a while-who is John Parker? This weird number is his only cinematic credit of any kind, and even that fact was being disputed by one of the actors, who claims he have directed parts of the film. While being a writer/director/producer of Dementia, for a long time he was only credited as producer.

Almost nothing else is known of him. Whoever he is, or wherever he is now, Dementia is a film that both the predecessors (Wiene, Murnau, Lang) and successors (Lynch, Maddin) would not be ashamed of.

10. None but the Brave (1965). Dir. by Frank Sinatra.

In Mario Puzo’s “The Godfather’, the crooner Johnny Fontane (largely thought to be inspired by Sinatra) tells Don Corleone of his wish to direct a movie, as a mean to bolster his sagging career. In real life, Ol’ Mickey Blue Eyes did get to direct a film-but it turned out to be his only directing credit.

Seems strange at first-Sinatra has turned in a well-made and coherent war film. The story of a Japanese army unit and a U.S. Marines platoon having to coexist in uneasy truce due to being stranded on the same island is presented here realistically, without mawkish sentimentality.

War is shown for what it is-hell, with few and far between incidents of humanity only serving to underline the senseless destruction and the waste of human lives. The Marines are presented without overt heroics, and the Japanese-not as a senseless enemy but as people, stuck in the same situation (the narrator of the story is the Japanese officer, writing a letter to his wife).

It bears much resemblance in spirit to “The Bridge Over the River Kwai”. It’s therefore kind of puzzling that it was met with a mix of indifference and hostility upon release. That resulted in it being little-known today, and that’s a shame-Frank succeeds on all levels here.

He seems fine with playing only a supporting role, is wise to employ experienced and talented collaborators (a young John Williams composed the score), and did present a clear and coherent anti-war message. The image of the smiley face drawn on the bandage that covers a stump of the amputee is undeniably powerful.

9. Everything is Illuminated (2005). Dir. by Liev Schreiber.

Schreiber stated that he chose to direct this film because the source novel deeply affected him and made him want to pay more homage to his Ukrainian-Jewish roots. Here’s hoping he reads more and gets more inspired.

For he managed a nearly perfect adaptation of Jonathan Safran Foer’s quirky and poignant novel, helming it with an assured confidence of a veteran director. He took a story of a neurotic and touchy New Yorker who goes to Ukraine to search for his ancestors and to find what happened to them during the war, and gives it the treatment it deserves, hitting all the right notes.

The American protagonist makes a misfortune of hiring the weirdest tour guides possible-a punkish Ukrainian lad, accompanied by his foul-mouthed, ornery, and very anti-Semitic grandpa, together with a mutt named Sammy Davis Jr. Jr., who take him on an unforgettable ride in their dilapidated, rusting bucket of screws of a car.

What made Foer’s novel such a hit was an effortless mixing of historical tragedy with fish-out-of-water comedy. An annoying and neurotic vegetarian hero is thrust into a rough and tumble madhouse of a land, where even vegetables aren’t vegetarian. All the necessary laughs are here.

Schreiber’s casting is impeccable-Elijah Wood is spot-on as the hero, veteran Russian and American character actor Boris Leskin is perfect as grandpa. For the narrator, the hilariously obnoxious Alex (“My English is not so premium”) Schreiber obviously needed a Gogol Bordello-inspired character-so he cast the predictably perfect Eugene Hutz from Gogol Bordello (more kudos to Schreiber for convincing Eugene to lop off his famed mustache, must have been an enormous sacrifice). Which naturally brings to the next best element-music.

Using the klezmer tunes of Paul Cantelon, the merry jingles of Gogol Bordello, and the classics of Russian punk courtesy of Sergey Shnur and Leningrad, Schreiber makes his film pulsate with absurdist energy.

The cinematography is fantastic, and the editing is, again, very assured. Purist lovers of the novel may bemoan the fact that Schreiber dropped the flashback to the XVIIIth century shtetl, but this decision is more than justified by the final result. Since then, Schreiber achieved fame and respect as an actor, but as of right now is in no hurry to direct again.