6. Flowers (Loreak, Jon Garaño and Jose Mari Goenaga, 2014)

Ane is a married woman that finds herself receiving flower bouquets weekly from a complete stranger. Far from being worried she seems to enjoy it since her marriage is going through a rough patch, but one day the deliveries stop. It is the beginning of an odd flowery adultery tale in which every deceived being knows only a part of the story. Fear, hope or new awakenings are the driving forces of this strange adultery that devastate their lives.

The film’s time treatment is, without a doubt, its best feature; it is a fundamental ingredient to test feelings born from love. Outlining the subtle direction carried out, showing little changes based on which one of the three leading roles is center of attention, alternating focus on their stories with gentle precision and employing typical thriller tools to achieve it.

It is true that the flower effect draws a parallel between the plot and Basque society, but “Flowers” goes beyond any kind of localism and emerges as an emotional journey of three; in one way or another, trapped women incapable of doing what it takes to bloom and reach full magnificence, whether it is a marriage gone adrift, solitude after a son’s death or one’s own sorrow denial that prevents them from moving forward.

A notable work with clearly established ideas knowing how to reflect tastefully and carefully its goals, achieving an unusual balance between form and substance.

7. To Return (Volver, Pedro Almodóvar, 2006)

Pedro Almodóvar arouses opposite opinions. Acclaimed by a big fraction of the audience and specialized foreign critics, in his own country he has the same amount of fans as he has detractors. In this film, Raimunda is a young and very attractive entrepreneur mother with an unemployed husband and daughter in her teens. The family economy is precarious, the reason for Raimunda having several jobs. She is a strong and tenacious woman but at the same time, emotionally fragile.

Events and environments to which Almodóvar has accustomed us: matriarchal society of provincial women, with their secrets, their alliances, women that are both friends, rivals and neighbors, always ready to give a helping hand in harsh times. Unsustainable becomes quotidian, rural and urban adventures in a mother-child based plot with several generations of characters distraught by a shady past and failed love relationships.

The weight of the past over present and how this is determining in irreversible and unexpected ways, again, black humor and a humanist point of view; east wind takes on a lead role with its omens of ghost, death and insanity stories, matters dealt with humor and warmth in their rural and humble context.

The Manchegan director introduces us into an odd story, with a script swamped with unexpected turns, grazing the unbelievable but making it credible due to the way the characters and their feelings are addressed to us. “To Return” is, at least initially and by location, of the works that deal with tragedy and film noir the most simple-crafted of them, but receives direct benefit of the artistic and technical aspect advances the director has achieved, clear in its impeccable visual finish.

8. Marshland (La Isla Mínima, Alberto Rodríguez, 2014)

Two young sisters have gone missing in a little town in the Guadalquivir marshlands in 1980, and a couple of police inspectors of opposed nature confront a serial killer in an hypnotic, fascinating, properly directed and balanced film. A balance that begins with the leading double role of Raúl Arévalo as the young and honest policeman, and Javier Gutiérrez, a more obscure character coming from the Francoist regime.

The classic police plot is used as a pure excuse to make a social depiction of the era, a historical moment in which Spain is already a democracy but still clinging to the past. The film shows a rural Spain marked by day laborer’s vindications, female discrimination, extreme poverty and other social issues.

The cinematography deserves a special mention; the Eye-View shots of Doñana Park and Guadalquivir’s south stream stand out conveying the landscape as sometimes serene and a suffocating one otherwise, whenever Alberto Rodríguez needs it to develop his storyline applying suspense in its precise dose. The fractal images by Héctor Garrido have turned out to be, not expectedly, an icon of the film.

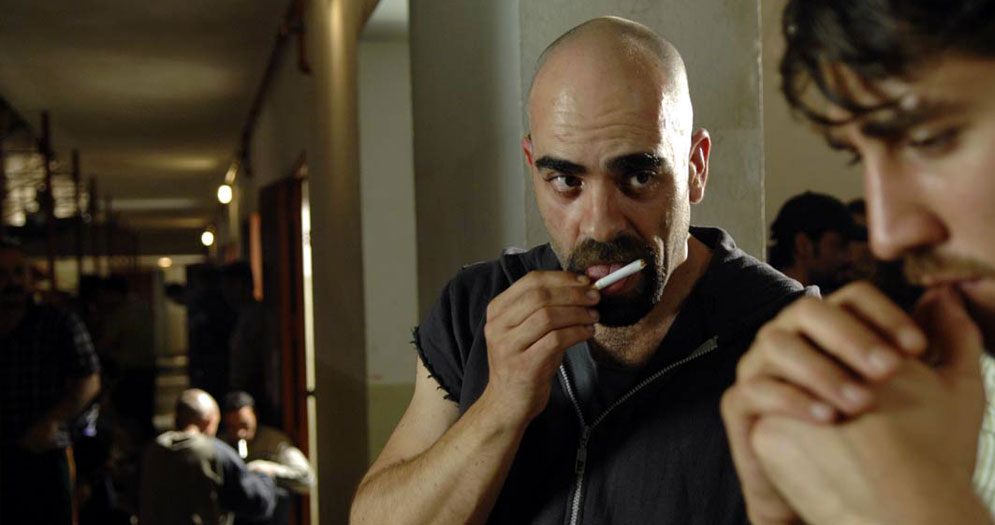

9. Cell 211 (Celda 211, Daniel Monzón, 2009)

The day Juan starts his new job as a prison officer he sees himself caught up in a mutiny, deciding to impersonate a prisoner in order to save his life and end the riot, led by Malamadre (overwhelming evolving character played by Luis Tosar), a charismatic hypnotic and fascinating beast in who brutality and an extreme code of personal values go together.

An intense film attached to the ground, raw and dramatic showing in realistic-style the inner life of a jail in the middle of a mutiny and depicting a sense of humanity in prisoners, civil servants and politicians hiding the best in individuals and also the meanest of passions.

A story that goes from social to personal when Juan gets fully involved in the riot events; authority abuse and improper negotiation when political interests intercede. Reality displayed with support of the country’s present and by the sympathy those innocent broken subjects arouse due to a deficient sociopolitical task.

In that particular case, Juan’s transformation into a criminal is a paradigm of life spoiled by negligence of one and inefficiency of others who don’t get right trading an innocent’s life and playing with it for partisan reasons. Daniel Monzón imposes spirit and poignancy into an always-powerful narration, achieving unsustainable pressure and visceral images in perfect unison but, unfortunately, with some weaknesses that block mastery, like the prison outskirts riot subplot seemingly unnatural to trigger an irreversible turn in the course of events.

In exchange, the director brilliantly uses three ETA members as a subtle McGuffin with no plot politicization menace, suggesting a moral collapse and also consistent ways that lead to an unsuspected fraternity between its two main characters. It’s a vigorous and solid penitentiary drama with complaint vocation dressed up in filthy aesthetics and an always hostile and rough setting.

10. Common Wealth (La Comunidad, Álex De La Iglesia, 2000)

Julia is a real estate agent, and her life will change one day when she finds a huge amount of money inside an abandoned flat. However, the building’s neighbors are also after the loot and will try, by all means necessary, to snatch it. Álex De La Iglesia mixes in this flick, at times, comedy, thriller, horror, action and adventure, presenting us an eccentric resident’s association willing to do anything to get 300 million pesetas.

Constructing a well-developed suspense storyline, with multiple references to Alfred Hitchcock or Roman Polanski, with daily but horrific characters and a truly smothering atmosphere, the viewer sees himself quickly captured inside the monster-filled building with no exit in sight.

This anguish is counteracted with humor, original dialogues and rationed action scenes. Comedy is the cruel enjoyment in front of other’s suffering and it is the only genre that allows to depict things other genres are incapable of showing; the director uses this premise to tell his story.

The cinematography and scenery are very important elements in story building and De La Iglesia knows it well; his films usually use mostly overloaded scenery and loud colors, and in “Common Wealth”, the building environment is oppressive and dark but the apartment where Julia is staying is totally colorful. The idea of constriction tries to make sense of the anxious situation the characters are locked in.

As Álex De La Iglesia himself put: “The thesis of my film is that the hardest drug today is money. My vision of current society is that we are all guilty because we all are greedy and envious. But worse to say is that nobody assumes the bad guy role because everybody, as it happens in my movie, justifies their money needs with all kinds of arguments.“

Author Bio: Marina Berlanga is a freelance artist from Barcelona, she loves films and manages to cancel all her plans to go to the cinema. Friends and family request bringing her back home if you see her in a movie theater.