5. Union Station in The Untouchables (1987)

In David Mamet’s screenplay, lawmen Eliot Ness (Kevin Costner) and George Stone (Andy Garcia) apprehend the mob bookkeeper and potential witness from his handlers by chasing his train, using their car to block the tracks, and climbing aboard for a firefight. This proved too expensive to film, so producer Art Linson asked for an alternative. Tired of endless studio demands for rewrites, and busy directing House of Games anyway, Mamet told Linson and De Palma to get lost – presumably using more robust vocabulary.

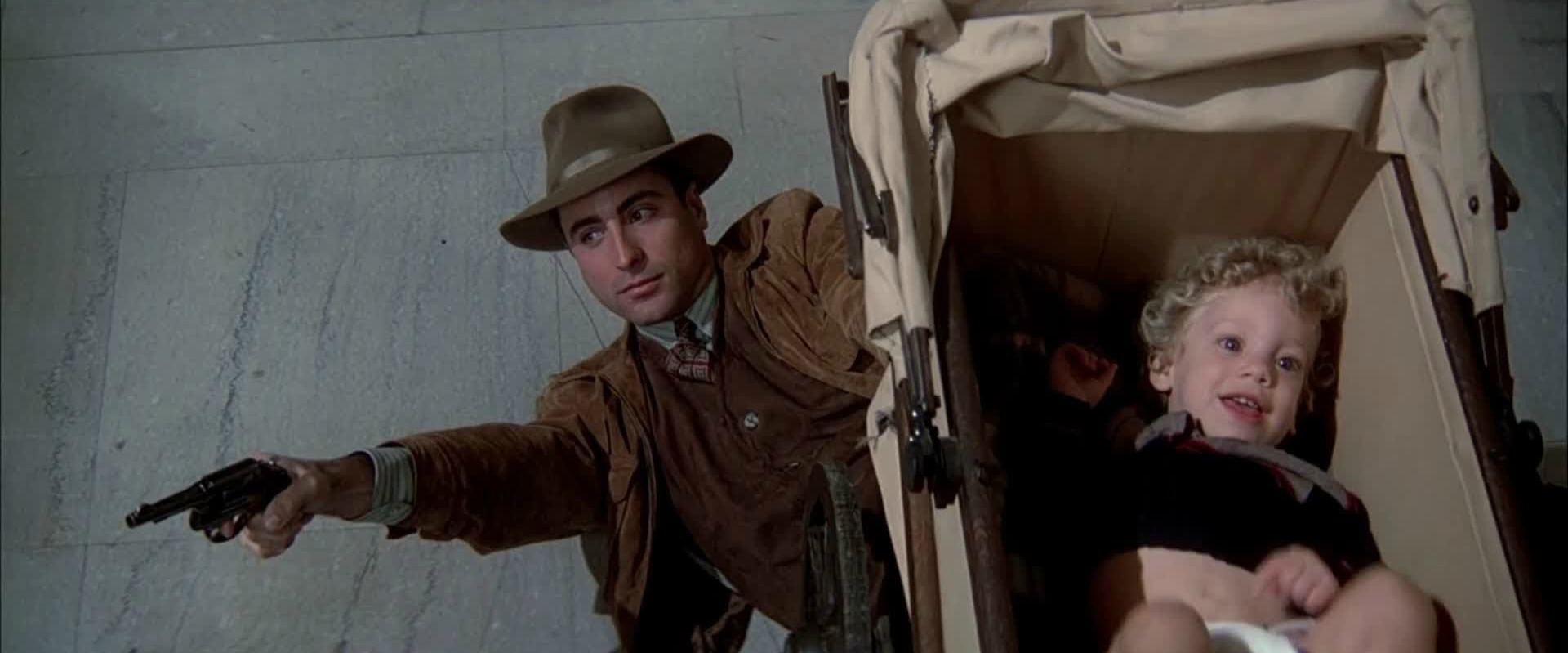

This meant not only reworking the scene but doing so without additional dialogue – Mamet’s coarse poetry being impossible to replicate. Once again De Palma looked to film history for a solution. He took Battleship Potemkin’s famous Odessa Steps sequence and placed it in Chicago’s Union Station, complete with runaway baby carriage and round spectacles on the bookkeeper.

In narrative terms, the film stops dead for four minutes while we wait for the mobsters to show up, cutting between Costner and his observations – the clock counting down to 12.05, the mother struggling up the steps with her pram and luggage, various suspicious characters – and while Ennio Morricone’s score evolves from a chiming lullaby to full orchestral menace. This is pure cinema, ratcheting up the tension with every cut – and, for the most part, using only a handful of camera angles.

But this isn’t style without substance. Ness is a by-the-book husband and father torn between traditional values and the brutal overreactions necessary to battle Al Capone’s mob rule. The further he strays from his moral code, the more people around him suffer. This sequence distils the conflict – his good deed, bringing the pram up the steps, blows his cover and puts the mother and child in danger as they end up surrounded by gun-toting villains.

The ensuing slow motion shootout is structured around the pram’s rattling descent back down the steps while Ness scrambles after it and bullets fly all over the place. Having carefully established the geography, De Palma is able to communicate the chaotic crossfire with perfect clarity. The kid inside the pram is, of course, oblivious to the carnage.

4. Wissahickon Creek in Blow Out (1981)

De Palmaniacs will find all the filmmaker’s preoccupations present and correct – voyeurism, alienation, sleaze, doppelgangers, technology, political assassination and the mechanics and morality of filmmaking itself.

Sound engineer Jack Terry (John Travolta) stands on a footbridge over Philadelphia’s Wissahickon Creek, recording audio effects for a Z-grade slasher movie. As he hears each new sound, he swivels a directional microphone to find the source. A strolling couple. A frog. An odd, metallic snap – to be identified later (it’s John Lithgow). An owl.

The sequence is beautifully photographed and edited by Vilmos Zsigmond and Paul Hirsch. The split diopter lens, which allows two focal points in a single shot, compresses space to move Travolta closer to the source of each sound, and the images are cut in a disciplined, rhythmic progression.

Then a car veers off-road and into the water. As Jack dives in to attempt a rescue, we glimpse another observer by the bridge – quietly suggesting conspiracy. Jack pulls working girl Sally (Nancy Allen) out of the car but fails to save her client, who turns out to have been a presidential candidate.

The cops and political advisors spin the ugly Chappaquiddicky facts into a more palatable tragedy – the tyre blew out, the governor died alone. Jack returns to his tape deck and replays the scene over and over, hearing a pop just before the blow out: he may have recorded a murder. When that second observer turns out to be a photographer (Dennis Franz in full sleaze mode, complete with stained wifebeater) Jack sees a way to prove his theory.

Blow Out is often considered “Blow-Up with sound” but The Conversation got there first. De Palma’s film is their progeny, equally concerned with image. (There are also shades of both Antonioni’s mod cool and Coppola’s catholic guilt.)

All three films are about men obsessively trying to understand an event by reconstructing its audio and/or visual remnants. Jack knows he has to match pictures to his soundtrack in order to show people what happened. As a consequence, we review this key sequence again and again throughout the film, and each time it achieves a new level of suspense – a growing tension between the emerging, appalling truth and the danger of knowing it.

3. Subway Chase/Grand Central in Carlito’s Way (1993)

In subject and form, Carlito’s Way is De Palma’s most traditional film – a big studio crime drama set in 1975 New York, elegantly told and with none of the eighties excess of its twitchy younger cousin Scarface.

Pacino returns to the De Palmaverse as Carlito Brigante, formerly “the J.P. Morgan of the smack business” but now older, wiser and liberated from prison on a technicality. Carlito just wants to go straight, raise some cash and leave for a new life in the Bahamas with old flame Gail (Penelope Ann Miller). But he’s doomed by his own stubborn adherence to the “code of the goddamned street” about which the street, ironically, could care less.

De Palma rattles through the melodrama and stages a number of terrific set pieces – an early deal-gone-wrong in a pool hall is worthy of this list – but more importantly concentrates on the characters so that, when our hero finds himself in a corner, you root for him to get away even though you know he’s narrating the story from his deathbed.

In the final half hour, Carlito finds himself surrounded by enemies and on the run, due to meet Gail at Grand Central to catch a train out of town. He flees onto the subway with four murderous acquaintances on his tail, and leads them on a merry game of cat and mouse along the train and around the terminal.

This was another sequence made up on the lam, relocated from the World Trade Center after the 1993 bombing. It’s familiar territory for De Palma, who shot subway suspense in Dressed to Kill and used train stations to great effect in Blow Out and The Untouchables.

But the climax of Carlito’s Way is more kinetic – a race against time, no slow motion, emphasis on choreography. De Palma called Pacino “an incredible mover… I couldn’t wait to get out and start shooting, just to see him walk around” and the floating Steadicam proves to be the optimum device for capturing the actor’s physical grace.

The chase is bookended by a pair of intricate tracking shots lasting around two minutes each. The first follows Pacino into the train; the second sees him move stealthily around Grand Central, one half-step ahead of the mobsters. The length of the shots tempts you to hold your breath and dares you to look away, and Patrick Doyle’s urgent score heightens the tension until, finally, the scene explodes into a spectacular firefight on the escalators.

2. Murder in an Elevator in Dressed to Kill (1980)

In a near-wordless 20 minute sequence, unfulfilled housewife Kate Miller (Angie Dickinson) embarks on an impulsive one-afternoon stand with a man who wears sunglasses in an art gallery, while a barely-glimpsed blonde stalker lurks nearby. Later, Kate rummages around the stud’s apartment in a post-coital daze and finds a doctor’s letter about a venereal disease. She leaves, calls the elevator and steps inside – just as the mysterious blonde emerges, unseen, from the stairwell.

This is De Palma’s 10,000 word dissertation on The Elevator, and his greatest ever use of dead space. First it’s a refuge, as Kate flees her tryst. Next it’s a confessional – Kate realises she left her wedding ring in the apartment and will have to go back. Then it’s a courtroom, as a mother steps in with her precociously judgemental daughter, who stares Kate into submission until they reach the lobby. Finally it’s a trap, as she rides back up to the seventh floor by herself.

The tension is driven by banality – the elevator’s up-down function, the repetition of camera angles and sounds, all delaying the inevitable. Then the door slides open and the blonde lurches in with a glinting straight razor. It’s a terrifying claustrophobic murder, but De Palma’s masterstroke is using the set piece to switch our perspective to a new main character – high class escort Liz Blake (Nancy Allen) who waits on the fifth floor with a client.

Liz proves her worth when the elevator opens to a bloodbath. Her client runs away, but Liz reaches out to the dying Kate – in dreamy slow motion – as the blonde killer hides to one side of the door. Then a glint of light from the razor draws Liz’s gaze to the mirror, through which she and the murderer lock eyes.

This is a turning point in the story, transferring our sympathies from one heroine to another. It’s also the quintessential De Palma set piece, with its slow build, damsel(s) in distress, provocative fever-pitch violence and technical precision. A masterclass in suspense.

1. The Prom in Carrie (1976)

Carrie’s prom sequence is the climax of De Palma’s work up to that point, and a spectacular precursor of everything to come.

When closet telekenetic and social outcast Carrie White (Sissy Spacek – set dresser, Phantom of the Paradise) and Tommy Ross (William Katt – Luke Skywalker, Star Wars auditions) walk into the gaudy, booby-trapped high school gymnasium, De Palma sets the standard for the rest of his career and reaches the kind of filmmaking heights that made Pauline Kael and Quentin Tarantino swoon.

The scene begins with ten minutes of genuinely sweet teen romance, as Carrie and Tommy ease into each others’ company, cautiously supervised by sympathetic gym teacher Miss Collins (Betty Buckley). Tinfoil decorations shimmer in the light – some stunning cinematography by Mario Tosi. The couple share a giddy dance, shot from a low angle to exclude everyone else. It’s enough to trick us into hoping for a happy ending – which makes the tension so much more unbearable.

The high school’s spiteful Mean Girl clique led by Chris (Nancy Allen) rig the Prom King and Queen vote to get Carrie up on stage, right under a bucket of pig’s blood. As Carrie and Tommy head through the crowd to receive their honour, the camera cranks into slow motion and De Palma shifts perspective to two observers: Tommy’s boyfriend Sue (Amy Irving) and Miss Collins.

It’s a beautiful sequence, simultaneously establishing geography and building suspense, as Sue notices the rope leading to the bucket and follows it to a crawl-space under the stage; before Sue can explain herself, Miss Collins drags her through the hall and bundles her out the door. Pino Donaggio’s score starts to race like a heartbeat until, under the stage, Chris pulls the rope – and douses the newly appointed Prom Queen in blood.

When Carrie unleashes her supernatural wrath, the mayhem is bathed in red light and ends with a hellish image of the waif-like Spacek framed against a raging wall of flames. This sequence is a tense, technical tour de force, a classic moment of seventies cinema, and a clear highlight of De Palma’s 46-year career.

Author Bio: Andrew Gunn is a director, screenwriter, playwright and cinephile based in Scotland. When he’s not hunched over a notebook mainlining caffeine, you might also find him working with the French Film Festival or Baltic Film Society. His movie tastes are broad, from Robert Bresson to James Bond, but he’s particularly fond of film noir, suspense thrillers and action.