5. My Dinner with Andre (Louis Malle, 1981)

Based on the lives of Andre Gregory and Wallace Shawn, My Dinner with Andre tells the story of two old friends who have not seen each other for many years, and have developed radically different views on life and human nature. Louis Malle illustrates the different ways that individuals go about finding meaning in their lives.

Wallace (Wallace Shawn) meets his old friend Andre (Andre Gregory) for dinner. The two have not seen or heard from each other for many years, in fact, Wallace has been avoiding Andre. Andre was once a well-known theater director.

After losing his inspiration to direct, he left to travel the world. Having stuck around New York over the years, Wallace has achieved only mild success. Andre recounts his travelling adventures and his experimentation with mysticism as means to fulfill his desperate search for meaning. Wallace proposes that man does not need profound spiritual experiences in order lead a life worth living.

Louis Malle depicts an engrossing conversation between two old friends, who have become strangers to each other, and attempt to reconnect. Wallace and Andre challenge each other’s notions of human fulfillment. Andre believes that modern man of the western world cannot lead a fulfilling life due to the absence of spirituality and connection.

Wallace cannot accept Andre’s claims, believing that man can find meaning in comfort, intimacy, and conventional activity. Without attempting to resolve the issue, My Dinner with Andre explores the notion of value with regards to human life.

4. The Turin Horse (Bela Tarr, 2011)

Inspired by a popular story describing the cause of the profoundly influential philosopher Frederick Nietzsche’s mental collapse, The Turin Horse illustrates mankind’s dismal struggle to overcome suffering. Bela Tarr suggests that having lost faith in “God,” mankind has been unable to hold onto meaning, and has thus lost his value.

According to the tale, one day, upon witnessing a hansom cab driver abusing his horse for refusing to move, Nietzsche is overcome with pity. He rushes over to intervene. Sobbing, Nietzsche embraces the horse and collapses. Nietzsche never recovered, and spent the remainder of his life in a catatonic state.

The Turin Horse depicts the life of the cab driver shortly following his encounter with Nietzsche. The driver (Janos Derzsi) lives on an isolated farm with his daughter (Erika Bok) in a cold and barren land. The two spend all of their time tending to the farm with nothing to eat but boiled potatoes.

Exhausted and in despair, the farmer and his daughter show no affection towards one another, and only speak when necessary. Their horse, which they depend on as a life-line to the world, refuses to eat or move. Having meager resources, the two struggle to survive a treacherous winter storm.

Adopting a nihilistic perspective, The Turin Horse explores the cause of man’s suffering. The farmer and his daughter miserably go about their day to day routine tending to the farm. Exhausted from their rigorous routine, and their constant struggle to survive, the two are unable to hold on to any hope.

Bela Tarr illustrates man’s inability to justify and overcome his suffering without a belief in “God.” The concept of God imparts to man a set of values, and with that, a prescription of how one should act. The Turin Horse confronts the viewer with a question: In a world devoid of faith, does human life have any value?

3. Wings of Desire (Wim Wenders, 1987)

Winner of the Best Director prize at the 1987 Cannes Film Festival, Wim Wenders’ romantic fantasy is a lyrical meditation on the miracle of human life. Wings of Desire portrays everyday human experience, from the pleasures of smoking a cigarette, to the throes of falling in love, as infinitely valuable.

Wings of Desire tells the story of Damiel (Bruno Ganz), an angel who longs for the human experience. As an immortal, Damiel has existed for eternity, before man, and before society. His duty is to bear witness to man’s existence, taking note of curious happenings, and occasionally bringing comfort to people in need.

Damiel begins to grow tired of observing mankind without the ability to physically interact with the world. After falling in love with a trapeze artist (Solveig Dommartin), he decides to give up his role as eternal observer to participate in and experience the beauty of human life.

Wim Wenders depicts humanity as beautiful, awe inspiring, and of infinite worth. Damiel is unsatisfied with the static existence of an immortal being. He longs for the wide range of human experience, such as being in love, the uncertainty of life, and the dynamic nature of mortality. Wings of Desire proposes that every day human experience is a miracle, more valuable than immortality.

2. Through a Glass Darkly (Ingmar Bergman, 1961)

Winner of the 1962 Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film, and Ingmar Bergman’s first installment in his “Faith” Trilogy, Through a Glass Darkly confronts the insufficiency of faith, science, and art in filling man’s existential void. Bergman affirms that love is the only grounding force capable of providing meaning in human life.

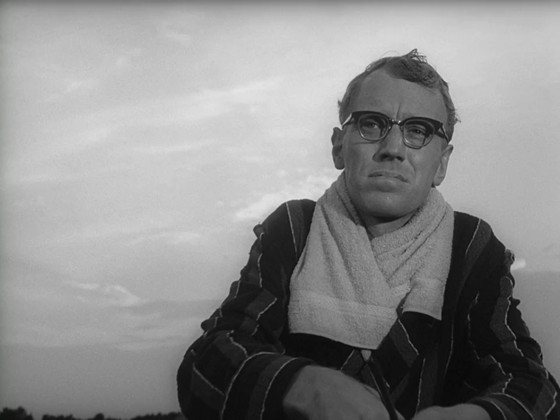

Karen (Harriet Andersson) has recently been released from an asylum where she has been treated for schizophrenia. She is joined by her husband Martin (Max Von Sydow), her father David (Gunnar Bjornstrand), and her younger brother Minus (Lars Passgard) for a vacation on a remote island.

Upon reading her father’s diary, Karen is overwhelmed by learning that her illness is incurable. She struggles to grasp onto any grounding force, as she drifts between two worlds. Forced to observe her descent into madness, Karen’s family grapple with their own lack of faith, certainty, and hope.

Through a Glass Darkly portrays love as the only force with the potential to ground man’s life with meaning. Afflicted with an incurable disease, Karen cannot depend on science or faith to provide her with answers. Bergman proposes that in the face of suffering, love may provide value to an otherwise painful existence.

1. Stalker (Andrei Tarkovsky, 1979)

Loosely based on the novel, Roadside Picnic, Andrei Tarkovsky’s alluring and illusive masterpiece explores the relationship between consciousness and reality. Using the “zone” as an analogy for nature at its purest unaltered state, Stalker contemplates man’s incomprehensible power to shape his own reality. Tarkovsky suggests that man both plays any role in constructing his reality, and is in some way responsible for determining the value of his own existence.

The “Stalker” (Alexander Kaidanovsky) believes it is his purpose to act as a shepherd to people by guiding them through the zone. The “zone” refers to a location where a mysterious event has taken place, altering the laws of reality within its vicinity. Deemed a danger to society by the government, the Zone is guarded by the military with deadly force. No one is allowed to enter.

The Stalker leaves his family for one last journey through the zone, in which he will guide a disillusioned writer (Anatoly Solonitsyn) and a professor of physics (Nikolai Grinko). On their journey through the zone, the Stalker struggles to explain the nature of the zone and its sensitivity to the thoughts, perceptions, and emotions of those who enter. The Stalker reveals that within the zone there is a room which can grant individuals their deepest wishes.

Tarkovsky essentially creates a thought experiment for the viewer, providing a unique context in which the audience can explore the connection between consciousness, reality, and the value of life. Reality in the zone is at least in part determined by the mental states of the individuals within it.

Tarkovsky suggests that man’s consciousness plays an essential role in shaping his reality. Further, the zone has the power to manifest an individual’s deepest desires, which frightens those who travel through the zone, because they fear exposing their true selves. Stalker forces the viewer to confront his own values, proposing that a meaningless existence is the manifestation of empty values. Can man establish sufficient values from which he can build a meaningful life?

Author Bio: Jonathan holds a B.A. in Philosophy from UCLA, and is currently pursuing a career in Journalism. On his spare time, Jonathan enjoys writing, kickboxing, and creating music.Check out his music on bandcamp: https://szamanka.bandcamp.com/.