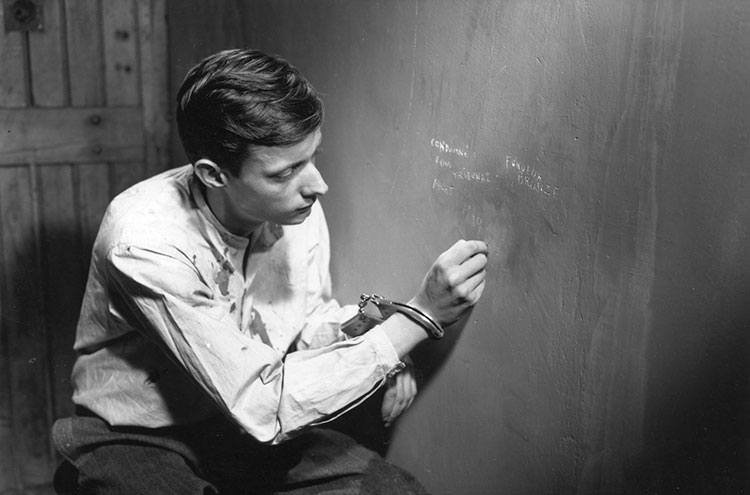

7. A Man Escaped (1956)

This film, one of the greatest prison-break films ever, is often overlooked by modern audiences, even though it’s a revered gem from the legendary French director Robert Bresson (Pickpocket, Mouchette), and one of his most personal films, too. During WWII Bresson spent close to 18 months in a prisoner-of-war camp, and this harrowing ordeal obviously informed A Man Escaped, which is largely based on the writings of French Resistance fighter and POW André Devigny.

François Leterrier is wonderful as Fontaine, a prisoner of the Nazis who’s discovered that he’s scheduled for execution. With very little time and complications cropping up constantly, Fontaine finds the inner resolve to hatch an escape and the ensuing flight to freedom is a masterful display of cinematic poetics and sublime understatement as is the breathtaking use of Mozart’s Great Mass in C minor.

6. Mr. Hulot’s Holiday (1953)

Jacques Tati, as ever, clearly illustrates how limited dialogue can still say so much. Taking his cues from greats like Harpo Marx and Buster Keaton, and falling back on his own early education as a mime, Mr. Hulot’s Holiday represents Tati’s inaugural turn as his famed screen persona Hulot.

The well-mannered and affable Hulot wreaks considerable havoc – not by design of course, by accident – at a seaside resort. Faster than you can spit “Mr. Bean” our titular Hulot has holidaymakers on frustrated edge as he bumbles through slapstick scenarios with both grace and aplomb.

5. The Driver (1978)

Walter Hill’s (The Warriors) stylish and electrifying neo-noir thriller, The Driver, is an influential actioner that’s aged marvellously well. Quentin Tarantino has referenced the film repeatedly in his work, and Nicolas Winding Refn’s Drive (2011) shares a tight-lipped and sententious stunt driver Xeroxed from Ryan Neal’s eponymous getaway driver herein.

Neal’s morally ambiguous anti-hero exists in an almost claustrophobic subterranean underworld of parking lots, filling stations, dangerous reprobates, a dodgy detective – namely Bruce Dern – as well as at least one risqué lorelei and potential femme fatale (Isabelle Adjani).

In The Driver, the overused adage that “actions speak louder” is given the gas pedal while the viewer is made implicit, riding shotgun all the way.

4. Under the Skin (2013)

A deeply thoughtful, penetrating, and profoundly shocking exploration of civilization and humanity, Jonathan Glazer spent nearly a decade on this dark hearted epic. Comparisons to Stanley Kubrick and Andrei Tarkovsky are appropriate and easily supported, as are the carefully constructed visual sensibilities and quasi-documentary leanings of Claire Denis and Lynne Ramsay.

Loosely using Dutch author Michel Faber’s satirical sci-fi novel Under the Skin as the alpha of this deep, metaphysical and mercurial treatise on, well, us, Glazer has surpassed expectation.

And for her part, Scarlett Johansson is outstanding, she shines in a zero cool, controlled and calculating process as she moves from childlike cherub to rouge-lipped iconoclast, all while saying very little. Under the Skin is a fascinating and hallucinatory experience, impossible to ignore, it worries, teases and taunts the viewer for days afterwards. Unforgettable.

3. The Silence (1963)

Often hailed as a linchpin of modernist cinema, Ingmar Bergman’s (Wild Strawberries) 1963 masterpiece, The Silence is a contemplative and in-depth study of alienation and estrangement between two sisters. Bergman’s trademark affinity for striking visuals pair with his taste for slow pacing as two troubled sisters, Anna (Gunnel Lindblom) and Ester (Ingrid Thulin) and Johan (Jörgen Lindström), Anna’s young son, find themselves moving through an unfamiliar city in Central Europe.

The emotional divide between the sisters deepens, and this is underscored by many scenes of unspoken frustrations between them, and the tide of war in their new dwelling seems certain.

Part of Bergman’s lauded Trilogy of Faith – along with Through A Glass Darkly (1961), and Winter Light (1963) – The Silence is a powerful, and perfectly realized creation from a master filmmaker during his peak.

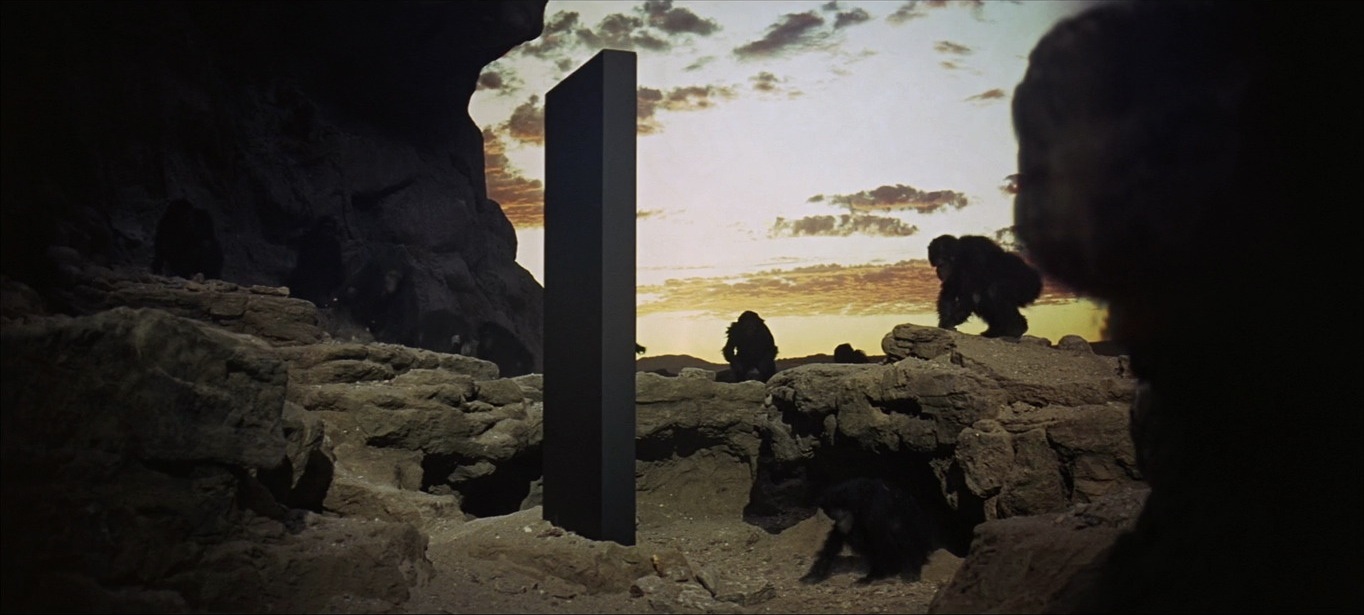

2. 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

“[With 2001] I tried to create a visual experience,” offers director Stanley Kubrick, “one the bypasses verbalized pigeonholing and directly penetrates the subconscious with an emotional and philosophical content.” Divided into three distinct episodes, 2001: A Space Odyssey, arguably Kubrick’s crowning work, he describes and details the emergence of new forms of existence as witnessed by an alien intelligence in the form of a brunet hued monolith.

Part one depicts the development from primate to man—no dialogue is spoken, nor is it needed—part two is the rise from artificial intelligence to sentience, and part three is the transition from humanity to something outside our territory, a star child, a new evolutionary leap.

While 2001 does contain many memorable sequences with excellent dialogue, the film is bookended with lengthy dialogue-free passages, deeply psychedelic and bolstered substantially by György Ligeti’s music and eye-popping visuals.

There’s probably no other film in cinematic history that so skilfully combines arthouse integrity with populist prestige. Formally untouchable, technically immaculate, and artistically overwhelming, 2001 is the finest science-fiction film ever made and its studied silences somehow speaks volumes.

1. Le Samuraï (1967)

The revered French filmmaker Jean-Pierre Melville (Army of Shadows) is known for his spare elegance and artful self-control, and nowhere are these strengths more evident than in his 1967 pièce de résistance, Le Samuraï.

Melville’s moody, melancholy characters aren’t exactly glib, and Alain Delon’s hitman, Jef Costello, typifies this idea. Melville too, it must be said, has an economical eye, here it closes in on Jef, a blasé and bewitching minimalist. Jef is a killer but there’s nothing excessive or ostentatious about him, profession aside, of course.

“Melville is god to me,” John Woo has asserted, on numerous occasions. “Le Samouraï was the first of his films that I saw… I’ve always tried to imitate Melville.”

Woo wasn’t alone, of course, Le Samuraï had a huge impact on Hollywood; films like American Gigolo, Drive, Ghost Dog, and Taxi Driver echoe and exhume much of what Melville accomplished herein. The pregnant pauses, the spaces between utterance, what goes unsaid and unspoken, all are of interest to Melville, who masterfully conjures a world and an atmosphere of transcendental elegance and ease.

Distinctively formal and popping with style, it might well be impossible to find a film as zero cool as Le Samuraï, a contemplative and quiet classic.

Author Bio: Shane Scott-Travis is a film critic, screenwriter, comic book author/illustrator and cineaste. Currently residing in Vancouver, Canada, Shane can often be found at the cinema, the dog park, or off in a corner someplace, paraphrasing Groucho Marx. Follow Shane on Twitter @ShaneScottravis.