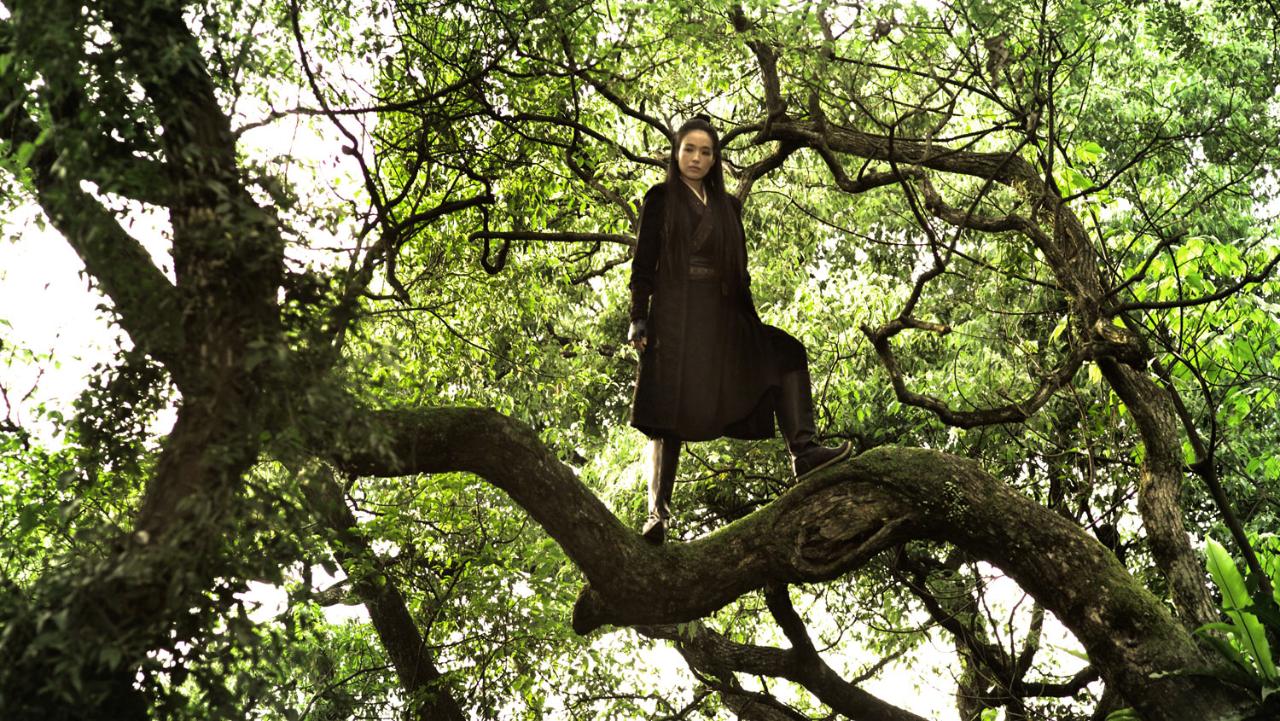

8. The Assassin (Hou Hsiao Hsien, 2015)

The Assassin is a wuxia film about an assassin who is supremely skilled in combat but still fragile in her heart and dominated by her feelings. Set during the Tang dynasty, the film uses the incredibly tactile style of cinematography of Hou Hsiao Hsien’s works, to create moving paintings inspired to the “Shan Shui” style, a technique of painting typical of the Chinese Tang period.

The landscape is dominated by mountains, forest and waters, the birds flying quickly above the waters, the breath of the wind through the trees, the mist embracing the mountains. The Assassin is a film about the tumults and the emotions that rage on the inside despite the calmness of the outside, and the landscape represents exactly that, carrying the emotional weight of the characters and the film.

The dominant emotion, symbolized by the recalling motif of the bluebird in the film, is the emotion of longing and melancholia, that spontaneously flows from the truthful and serene depiction of nature. Nature has within itself the notion of passing time and sadness, and Hou Hsiao Hsien lets it emerge through a pictorial style that allows the tiny details and the almost imperceptible soundscapes to tell the story of mankind and the story of the universe as if they were one.

9. Onibaba (Kaneto Shindo, 1964)

One thing that everyone remembers about the Japanese horror movie Onibaba is the iconic fields of reeds where the story takes place. The reeds dominate the landscape vigorously, and carry philosophical and socio-political connotations with them. The reeds are taller than men, and create a forest-like setting where characters get lost and then meet the ultimate fate.

Kaneto Shindo uses the literary topos of “locus horridus”, a concept that runs through literature and refers to the forest as an idealized evil place. The reeds become an existential location to represent the existential horror of post-war Japan, a country that feels lost and in a mysterious and dangerous world.

The Onibaba ( demon hag ) represents death, that deprives Japan of its youth, the mask is a reminder of the deformity caused by the nuclear bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The other elements of the landscape, wind and the scarcity of sunlight are all reminders of impending doom, ominous signs of the dangers of the world.

The augmented sense of disorientation that the seemingly all identical reeds create adds to the paranoia and anxiety of Japan. The entire political and cultural outlook of a specific time period is portrayed through an apparently minimalistic landscape that carries in itself numerous metaphorical ramifications and has a deep psychological influence on the viewer.

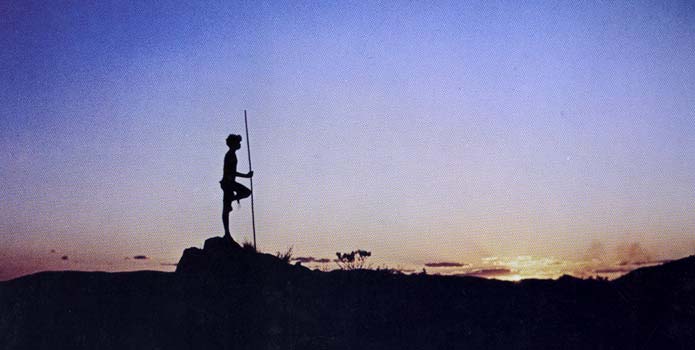

10. Walkabout (Nicolas Roeg, 1971)

Walkabout reveals the underlying horror beyond the apparent serenity of the landscape, and away from the protection of civilization. The film’s plot is very minimal, it was famously written on a fourteen-page script, and it is about a young pair of siblings from a middle class Australian that get lost in the wilderness. The traumatic experience of the two young protagonists allows the film the investigate the fear of nature that inhabits the urbanized part of Australia.

Roeg uses slow pans to show the vastness and stillness of the landscape, then uses extreme zooms to show us what happens underneath that initial impression. Using a technique that has connections with expressionist cinema, Roeg emphasizes small details in order to create a sense of repulsion and show the disturbing qualities of nature. He shows us creatures crawling, the endless game of death, of hunter and hunted, that constitutes the daily routine for the many wild animals.

When Roeg shows the viscera of a dead animal, he is showing the fundamental, naked look of nature, which is hidden behind the lies of organized society. When the girl comes back to civilization, she can see it for the lie that it is, and the image that stands as the representation of pure truth , is the two protagonists naked at the center of a lake. Man and landscape, together without separation, constitute the true essence of existence.

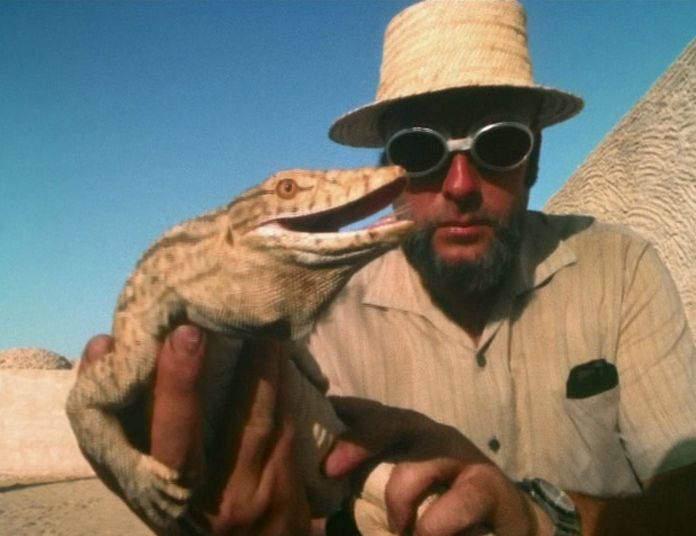

11. Fata Morgana (Werner Herzog, 1971)

Fata Morgana shows Werner Herzog at his most abstract and expressionist. Fata morgana is the name given to an optical illusion, a superior mirage, that is seen on the horizon in the desert. The images of the landscape are accompanied by quotations from the Popol Vuh, the Mayan book of Creation. The possible divinity of nature and the spirituality of the landscape are examined.

Herzog is literally filming an illusion and the gaze of the camera ponders about whether the entire nature is an illusion, a divine trick, a failure of the intellect, or something substantial. The human element is featured sporadically, and the inquisitive camera constantly scans the weird, impenetrable desert landscape and the horizon, trying to look beyond the veil imposed by human limitations, trying to see inside the womb of the universe.

The film is about nature and what’s beyond, about the appearances, the vest of nature, and to explore this themes, shows the landscape in all its inflexible mysterious glory, and lets the eschatology of it all emerge from pure contemplation.

12. Silent Light (Carlos Reygadas, 2007)

Silent Light is set among the community of the Mennonites, a Dutch speaking enclave that inhabits Mexico. It is story of a love triangle and an exploration of the concepts of love and devotion. It is also a celebration of the landscape and the search for the truth inhabiting nature.

To look for this truth, Reygadas goes for an extreme elongation of the shots of the land, particularly the very first shot that lasts about five minutes, that shows the dawning of the sun and the passage from the state of darkness to the state of light.

Instead of fragmenting the landscape in a series of shots of medium length, Reygadas tries to emulate the heartbeat, of the land, its rhythm, so that the cries, the whispers of the creatures, the flickering light, the stars, the howling and the shadows can create a vision that is as complete as possible, and therefore true.

The visions of the landscape in Silent Light have the monotonous, indifferent, quiet pace of existence. The rhythmic symbiosis that is established between the eye of the camera and nature create a depiction that is as close as possible to the real state of existence, the concept of Being.

Even the characters appear to share a connection with the land; in one of the key scenes one of the characters has an emotional breakdown that is echoed by a rainstorm, creating the sense of emotional solidarity between man and nature, as if they’re both weeping at the same time. The Mennonites through their deep spirituality, appear to be not just a product of nature, but an integral part of it.

13. Sunchaser (Michael Cimino, 1996)

Sunchaser, the story of a former convict who is dying of cancer and a self-absorbed doctor who is forced to travel with him to a Navajo site in Arizona is a film about personal identity, but also national identity.

Michael Cimino belongs to the American primitivism artistic movement, in a cinematic way. He believes in the hypnotic, uplifting power of the American landscape, he believes that the true identity of the American people is to be found in the Native roots, in nature, not in their industrial and economical past.

The journey towards the Navajo country unfolds between deserts and canyons, until the final liberating run under the gaze of an eagle, in a green rocky valley, and the film finally gets the naturalistic vision of America it was ailing for: blue lakes, brown mountains with snow on top and a clear sky.

The landscape also becomes a symbol of freedom, as the two characters call back to the American cinematic tradition of the romantic outlaws in noir films and western films. Reaching nature going out of the laws of society and into a new dimension that is individual instead of collective.

14. Tropical Malady (Apichatpong Weerasethakul, 2004)

Tropical Malady is a film about love story between two men that begins in the countryside and then moves to a jungle full of darkness, tiger shamans, spirits of cows, otherworldly sounds and mysterious lights, where the two characters get progressively lost.

The jungle in Tropical Malady, is a place of heightened perceptions, everything pushes towards an oneiric dimension. The jungle represents both the vast intricate nature of the physical universe, with its infinite intricacies, and depths of human memory and of human desire.

The landscape is wrapped in surreal darkness for a good part of the film, giving the sensation of reaching deep into the profundities of the human psyche and soul. The jungle is a non-place, a subconscious territory, and at the same place the representation of the complexity of the entire universe.

The primary quality of a jungle environment, the swallowing of the light, the precariousness of the vision that’s caused by the intricate trees and leaves, is here used to reach an abstract representation of life. It is also a symbol of everything that is magic and irrational in the world, including human desires, as Weerasethakul said that “The paranormal lives within the jungle”.

Tropical Malady is a metaphysical tale of love and memory but also a dark fairytale, and it all gravitates around the mysterious landscape and the way the human figure can get lost in it to a point of not distinguishing the connotations of the real anymore.

15. The Tree of Life (Terrence Malick, 2010)

Malick is the anti-Herzog. Where the German director finds desperation, sadness and chaos, Malick finds happiness, purpose and salvation. Malick’s cinematic philosophy is comparable to the thoughts of Dutch 17th century philosopher Spinoza, who said that “Deus sive natura”, latin for “God is nature”.

Malick finds divinity in nature, he has pantheistic aspirations, and the the Tree of Life is a film about humans, namely two parents struggling to cope with the death of their child and the coming of age story of one of the sons, but it is primarily a film about Beauty, a romantic concept of Beauty that coincides with the Absolute Being.

Malick is comparable to Romantic and extremely lyrical poets such as Holderlin and Riilke. Lubezki’s cinematography illuminates every vision in the film, from microscopic molecules, to entire nebulosas, from hammerhead sharks to volcanoes: Malick shows us the glory of the cosmos, and even when filming the urban environment of a small Texas town, he reaches for the open spaces, the skies and the plains.

The landscape is everything, quite literally; to Malick, a sunflower is a bearer of collective salvation. The landscape is venerated from the first shot to the last shot of the film, everything is perfect. “We are in the best of the possible worlds”, said the German philosopher Leibniz, a contemporary of Spinoza.

Malick represents the universal landscape triumphantly, and does so by letting the camera revel in the beauty of it all and letting the lenses shine a light on everything that exists.