While we all might like to think there is some dysfunction in our own families, it is often the Modern Family type of dysfunction—sit-com kind of stuff. Dad is crotchety, mom dances badly and unashamedly, and the kids are snarky. On the other side of the coin, though, is familial dysfunction the likes of which we’d rather not know about.

Alcoholism, abuse, both emotional and physical, lost love and abhorrent insensitivity plagues too many family trees around the world. But we don’t really want to get that real.

Instead we turn to those magicians of visual storytelling, the magnates of the silver screen, the artists behind the most powerful medium existing today, filmmakers, to illustrate not only what dysfunction plagues the family unit, but how it can show us something universal in our experiences on this planet. Here are twenty examples of the most dysfunctional families in movie history.

20. Mommie Dearest (1981)

Based on the tell-all book by Christina Crawford, Mommie Dearest s the bitter beans about growing up as Joan Crawford’s child, but this isn’t a conventional biopic, filled with pop psychology and “triumph” and “realism.”

Instead we get that gossipy, usually fabricated sensationalism that screams from the pages of tabloids. Director Frank Perry, without trying too hard to make the film conventionally coherent, lets each scene play out to its illogical, and yet still emotionally logical, conclusion. The whole point here is to see Joan Crawford versus Christina Crawford, mother versus daughter.

There is a very lonely side to celebrity that is explored in Mommie Dearest, too, and this loneliness gives way to madness. It suffocates the Crawford family, Joan lost to an unidentified dementia and Christina stuck mopping up after her.

For all the dirty laundry aired out in Mommie Dearest, its lavish sets are lushly colored. Perry’s biopic jumps back and forth from tasteless B-moviesque mania to tactlessly thoughtful, unabashed entertainment. Mommie Dearest is the kind of dysfunction we eat up, like a guilty pleasure, or just dessert. It’s Camp, in all its glory, though like sleep away camp, we might cry at first, only to not want to leave when it’s over.

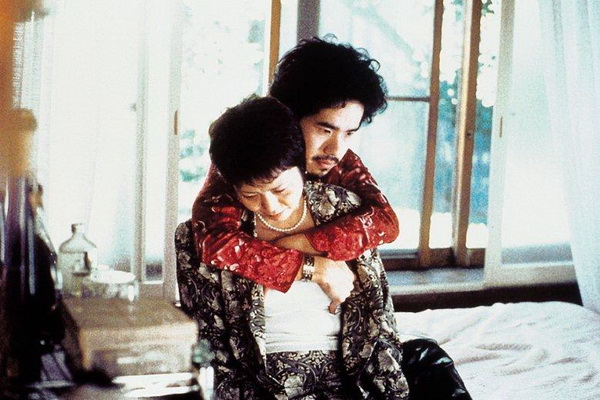

19. Visitor Q (2001)

Takashei Miike’s Visitor Q is really gross. The story centers on a mysterious visitor to a family struggling to coexist. The dad is a journalist working on a story about teen bullies (teen bullies have tormented not just his son, but him, too). Mom lives in fear of her abusive son, and their daughter has run away from home to turn tricks (including to her father).

The visitor doesn’t object to the behavior, but somehow helps the family rediscover their hierarchy, allowing mom to get back in touch with her maternal side (and her breasts), giving dad his backbone, and bringing the children back to the parental tit. The fact that everything is still incredibly fucked up after the ship has righted is Miike’s special touch, proving that even the craziest of family’s need to rediscover their love for each other, once in a while.

Miike’s take on the dysfunctional family is bonkers even to the bonked, though what do we expect from the director who brought us Audition and Ichi the Killer?

18. The Color Wheel (2011)

The Color Wheel is a timeless road trip comedy about a pair of siblings that hate each other. JR is a young woman floating through life, fresh off a break-up with her college professor, floundering as she awaits a job in broadcasting, or acting, or whatever will get her on television. Her brother, Colin, has given up hope on living a unique life, settling down with his girlfriend of three years, living in his parents’ attic so he can save money for a prudent life.

You’d think they couldn’t be more different, but Colin and JR are both snarky, witty, and wallowing in self-pity, and both jump at the opportunity to hit the road on a quest to get JR’s stuff back from her ex-beau and do anything else that will keep them away from their respective realities.

Alex Ross-Perry and Carlen Altman wrote this feature together (Ross-Perry directed it), play the lead roles (Ross-Perry as Colin, Altman as JR), and bring enough perky comedic timing to carry the film. Offbeat doesn’t quite describe The Color Wheel adequately, though it will have to do. The jokes are delivered in motor-mouthed dialogue that is tinged with an out-of-place sexuality, only to reveal its purpose in its provocatively taboo ending.

The Color Wheel feels like it came from nowhere. Shot in black and white, capturing America without naming it, with a soundtrack of hits different generations would recognize, the entire aesthetic is begging for anonymity.

What is most clever is Ross-Perry’s idea of two siblings knowing each other so well, they are meant for each other, even if they profess a deep resentment for one another. Dysfunction has never been so finicky.

17. Julien Donkey Boy (1999)

Made with a nod to the “Dogme 95” pact (created by Danish filmmakers Lars Von Trier and Thomas Vinterberg, they demanded handheld camera work, on location props and shooting, and natural lighting and sound as a way to reconnect with the purities of honest filmmaking and storytelling), Harmony Korine’s Julien Donkey Boy is a poetic assortment of imagery, a messy movie, and a touching, painful and funny portrait of a schizophrenic and his family.

Julien is the schizophrenic, living with his father (played by Werner Herzog), pregnant sister (Chloe Sevigny), aspiring amateur wrestler brother, and a spooky grandmother.

Korine’s disorienting film isn’t always lucid, even after giving it the necessary slack. It splices in events—like a random performance from a cigarette eater, or an armless man drumming using his feet—that have nothing to do with anything, taking on a quality of a movie like Freaks, without the substance. But Korine experiments with film in a way few filmmakers do, and Julien Donkey Boy certainly elicits a strong reaction.

Julien’s experience is the most thoughtful. We see the movie mostly from his perspective and, in essence, we’re living life as he lives it. In this way, Juilen Donkey Boy is a sympathetic lens for schizophrenia, caught in Korine’s net of provocation, lost in misfit moments, but convincingly sincere—dysfunction humming along like a well-oiled machine.

16. Track of the Cat (1954)

William Wellman’s Track of the Cat begins with a figure out in the large, snowy expanses of 1880s northern California (though it was shot in Washington, and not in 1880). It might remind us of the infinitely larger desert expanses of Lawrence of Arabia, but quickly we are shut in to the tight confines of the Bridges’ family ranch house. This claustrophobic melodrama is referred to often as a western, though that may be based strictly on the horse saddles.

On the ranch we find Curtis Bridges (Robert Mitchum), the eldest son and de facto patriarch of the family. Pa is a drunk and Ma is married to the lord and frightfully bitter. Grace, the lone daughter, hates Curtis’ iron fisted rule, and brother Arthur is a more spiritual sort, hoping everyone can just get along. Then there is the youngest, Harold, and his love interest, Gwen. Track of the Cat is mostly about Harold’s coming into adulthood, taking the mantle as head of the household from his tyrannical brother.

The dysfunction in the Bridges house is cut with a deep-seeded fear of what lurks out in the snow. A large black panther (pronounced “painter” for some inexplicable, possibly dialectical reason) is roaming the area, killing their livestock, but hunting them, too.

The panther gives Track of the Cat a ghostly feel, like something is scaring this family into behaving as maniacally as they do. Their dysfunction is their own doing—trapping themselves in with nothing but snow, booze and resentment—but the terror brought upon them by the skulking black cat holds them close together.

15. Out of the Blue (1980)

Dennis Hopper’s Out of the Blue defines the dysfunctional family as a drunken circus of animals. It is nearly impossible to explain the crookedness of the story. A dad, fresh out of jail after a horrible accident involving booze, a truck, a school bus full of children and a monkey, comes home to his adulterous fish of a wife and his rebellious daughter.

The film is really about the daughter, Cebe, who runs away and experiences the gritty side of gutter life. Better than being at home where mom and dad, in a flash of parental brilliance, decide to pimp her to a friend to relieve her of her virginity.

Out of the Blue is really great, because it is a unique project shelled in a plot straight out of an asylum. Cebe’s adventure takes on a documentary feel, capturing real life within her fictional one. With all that is happening back home, it is a real question as to whether Cebe is better off fighting for herself on the streets over being with her demonic parents. If a family can be this dysfunctional, maybe it’s best to blow the whole thing up.