8. Under the Skin (2013)

Working from Michael Faber’s 2000 pitch dark tragicomedy sci-fi novel of the same name, Jonathan Glazer’s Under the Skin is an altogether different beast. With the formal grace of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, the quasi-documentary and carefully composed sensibilities of Claire Denis (Trouble Every Day), and the slow cinema spirit of Lynne Ramsay (Morvern Callar). Glazer’s ambitious art film, nine years in the making, may echo the aforementioned auteurs, but make no mistake, this is a jaw-dropping original work of artifice.

Controlled, confident, and cool, Scarlett Johansson is the ultimate voyeur and severed outsider as a female extraterrestrial – in the film she has no name though in Faber’s novel she goes by Isserley – she hunts and destroys working-class men that she cruises for in her nondescript van. These men she seduces aren’t necessarily deserving their cruel fates, moreover they’re easy marks played largely by unknowns and non-actors.

Glazer hid some eight cameras in Johansson’s van and had her approach real passersby on the street (afterwards they were approached by the production to secure permission and payment). This bold foray into surveillance cinema adds to the provocation and authenticity of what could best be described as a totally unaffected nightmare.

Under the Skin is an elaborate and ethereal experience, an ambitious arthouse horror film that’s as unnerving, senses-rattling, and strange as it is polarizing and unpredictable.

7. Body Double (1984)

Body Double is vintage Brian De Palma at his subversive, sleekest, and trashiest best.

Following Jake Scully (Craig Wasson), a B-actor of bad horror films who’s fallen on hard times, his actor pal Sam Bouchard (Gregg Henry) takes pity on him and hooks him up with a sweet gig house sitting at a luxuriously modern home high in the Hollywood Hills.

Toying with familiar Hitchcockian themes of voyeurism and obsession — sure, both Rear Window and Vertigo are mercilessly mined — the resulting erotically-charged thriller is a full-tilt charge of ghoulish glee as Jake’s house sitting charge comes with a telescope and a neighbor who does sexy stripteases nightly in front of her bedroom window, with the curtains wide open, of course.

The subsequent mystery, full of twists, turns, incredulity and intrigue, is a master class in misleads, narrative leaps, flashbacks, panache and put-ons in an airtight plot that’s full of deceit. Body Double is an intoxicating, and capricious caper that joyously goes too far, and is punctuated with a stellar turn from Melanie Griffith as porn star Holly Body. 80’s cinema was seldom so smart ass and enterprising as this wonderfully cheesy objet d’art.

6. The Conversation (1974)

Francis Ford Coppola dominated 1970s American cinema with the first two Godfather films and the war epic Apocalypse Now, but his provocative, cynical, and somber thriller The Conversation—itself a riff on Antonioni’s Blow-Up—is every bit as incensing and refractive as those larger scale pictures.

Gene Hackman is genius in his internalized and nuanced turn as surveillance expert Harry Caul. More at ease as an eavesdropper at a safe distance then actually interfering with people face to face, Harry is a hangdog antihero, lonely and secretive, he overhears and records a conversation with sinister overtones. The surveillance tapes seem to suggest something criminal, perhaps life threatening and Harry and the audience are soon swept up in a chimeric mystery.

As a postmodern study of voyeurism The Conversation is a first-rate film and one which anticipated the Watergate scandal with striking similarity and feelings of dishonesty, spying, and governmental corruption. Harry’s obsessive investigation gets out of hand with tragic results that nonetheless hold the viewer spellbound and uneasy as the intrigue deepens.

In our modern milieu, The Conversation is a film that has aged incredibly well and seems more relevant and frighteningly realistic than ever before, and it’s last image is a haunting and heart-rending tableau of delusion and desolation.

5. Blow-Up (1966)

Director Michelangelo Antonioni became an international filmmaker with this satirical strike on fashion, music, sexuality, social mores, modern sophistication, ennui and emptiness. Based on a short story by Julio Cortázar, Antonioni’s Blow-Up centers on mod London photographer Thomas (David Hemmings). His photographs are a strange mélange of artful vérité compositions of transients and migrant workers or chic fashion models whom he seems to hold in contempt.

While hungrily snapping away at a park Thomas finds himself drawn to a couple, an older man and a much younger woman (Vanessa Redgrave), whom he photographs rather intrusively, drawing the ire of the woman, Jane, who ends up dogging his trail in pursuit of his film.

With a thriller-style hook, Thomas, who’s frequent behaviour with his photographic subjects and those in his orbit, is increasingly alienating, begins to analyse his photos in the park which more and more take on a sinister slant. Is that a gunman lurking in the foliage? Is that a corpse in the undergrowth? As his photos develop and his paranoia takes hold it seems more and more likely that Thomas has captured a crime on camera.

Antonioni’s portrait of swinging England, a society self-absorbed and overrun with giggling groupies, impassive audiences, and Discordian performance artists amongst others, makes for a fascinating, troubling and beguiling mystery where voyeurism intersects with uncertainty, and answers are elusive and eccentric at best. A classic.

4. The Lives of Others (2006)

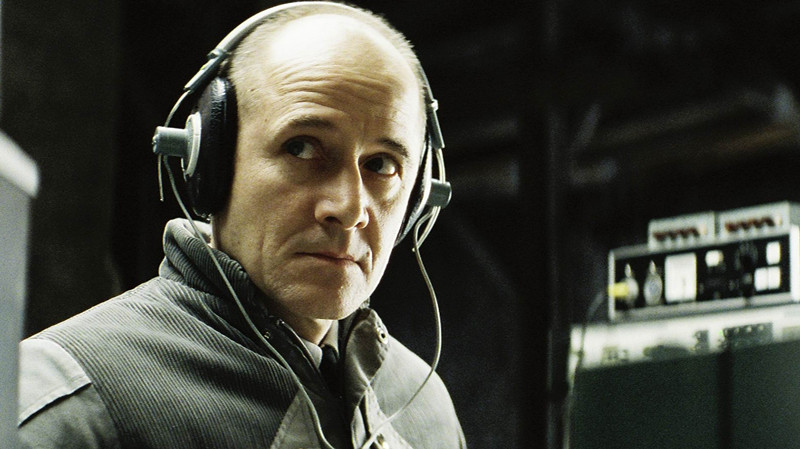

Alternately funny and frightening, Florian von Donnersmarck’s dizzying directorial debut, The Lives of Others, is a chillingly conveyed masterpiece.

Set in 1984 in Cold War East Germany, veteran character actor Ulrich Mühe (Funny Games) astonishes as Stasi hardliners Gerd Wiesler who’s taken it as his charge to keep potential dissenter and playwright Georg Dreyman (Sebastian Koch) under close surveillance.

The obsessive and unhealthy mindset of East Germany at that time, vigilant government-sanctioned spying and stalking, keeping tabs on its populace, tracking their every move with paranoiac fealty, is here portrayed with fascination, pathos, and incongruity.

Von Donnersmarck wisely plays up the Kafkaesque absurdity of the situations—based off of actual incidents—resulting in a richly rewarding viewing experience.

3. Peeping Tom (1960)

“I have always felt that Peeping Tom says everything that can be said about filmmaking,” enthuses admirer Martin Scorsese, “about the process of dealing with film, the objectivity and subjectivity of it and the confusion between the two. Peeping Tom shows the aggression of it, how the camera violates.”

When Michael Powell’s (The Red Shoes) Peeping Tom was initially unleashed back in 1960 it was met with near universal derision and contempt and famously destroyed Powell’s considerable career.

A disturbing and challenging psychological thriller cloaked in moral ambiguity, Powell’s film presents a troubled young man, Mark Lewis (Carl Boehm, brilliant), who leads his quarry, susceptible young women, into thinking he’s a documentary filmmaker. But Mark’s camera has a lethal metal spike attached to it, which he uses to murder his subjects.

Released the same year as Hitchcock’s similarly convergent shocker Psycho, both films feature troubled, repressed, dangerous young men with sympathetic and amiable qualities who nonetheless are vicious killers.

Mark uses his curious camera to capture his intrusive emotional state, foisting his troubled past onto his lovely young victims on ways that suggest a vérité style, making the viewer almost complicit in the garishly depicted offences, as if the very act of watching the film somehow enables Mark’s bloodlust.

No doubt so vile a suggestion is what upset audiences and critics at the time, when such perversity and savagery was a rarity and Powell’s obvious skills and craftsmanship as a visual storyteller, in the past used for uncensorable and innocent cinema all of a sudden so red in tooth and claw.

2. Blue Velvet (1986)

Entrenched with seeming innocence in small-town America, David Lynch’s darkly disturbing Blue Velvet courts controversy as much as it parades sickness and sadism. Beneath the well-manicured lawns and white-picket fences of Lynchian middle America, in this case the idyllic bliss of Lumberton, there lurks horror, hurt, danger and death.

Jeffrey Beaumont (Kyle McLachlan) and Sandy Williams (Laura Dern) are naïve youngsters, a romantic tension builds between them but so does a mystery as they do some amateur sleuthing in their sleepy little town.

Jeffrey has returned to Lumberton from college, owing to his father’s recent stroke, and he’s barely back in town before he makes a startling discovery; a severed human ear in the field near his father’s hospital. His curiosity, arguably unhealthy, soon finds him embroiled in the life of put-upon lounge singer Dorothy Vallens (Isabella Rossellini), whose husband and child have been taken hostage by wolffish psychopath Frank Booth (Dennis Hopper).

One of Blue Velvet’s most memorable scenes finds Jeffrey hiding in Dorothy’s closet, a perverse Peeping Tom, he witnesses Frank’s savagery first hand and is powerless to intervene. As far as onscreen voyeurism and surveillance is concerned, Blue Velvet is a masterclass and arguably Lynch’s finest and most unforgettable film.

1. Rear Window (1954)

“I wonder if it’s ethical,” muses photojournalist Jeff Jeffries (James Stewart), “to watch a man with binoculars and a long-focus lens?” Jeff is sidelined with a broken leg and bound to a wheelchair as he recuperates, and during this recovery period he’s got himself addicted to spying on his neighbors in Alfred Hitchcock’s masterful thriller Rear Window.

A finer and more fascinating study of obsession and voyeurism you’re unlikely to find and ol’ Hitch seems to luxuriate in the postmodern scenario he’s constructed—adapted by screenwriter John Michael Hayes from Cornell Woolrich’s short story “It Had To Be Murder”—which doesn’t shy at all away from playful sexual innuendo and pitch-black humor.

“We’ve become a race of Peeping Toms. What people ought to do is get outside their own house and look in for a change,” quips Stella (Thelma Ritter), Jeff’s home-care nurse, in what easily amounts to the ultimate experience in voyeuristic cinema and is also one of Hitch’s finest films.

François Truffaut famously wrote that “[Rear Window]’s construction is very like a musical composition: several themes are intermingled and are in perfect counterpoint to each other — marriage, suicide, degradation, and death — and they are all bathed in a refined eroticism,” thus detailing how the film, like the tenants across from Jeff that he can’t help but spy on, contain clandestine and diversified intentions, some healthy, some sinister, all engaging and with much hidden beneath the surface.

A slow-burn suspense thriller with a lot on its mind, Rear Window is a scathing study of contemporary society with a spy game the viewer gleefully and guiltily takes part in.

Hitchcock manipulates the viewer to a dizzying degree, making one question what they’ve seen, while slyly hinting at a great many moral divisions, from feminist protocols, social conduct, and the etiquette of neighbors, even notions of misandry, and heroism. There’s no other film quite like this, and it’s no wonder that it’s often considered Hitchcock’s pièce de résistance.

Author Bio: Shane Scott-Travis is a film critic, screenwriter, comic book author/illustrator and cineaste. Currently residing in Vancouver, Canada, Shane can often be found at the cinema, the dog park, or off in a corner someplace, paraphrasing Groucho Marx. Follow Shane on Twitter @ShaneScottravis.