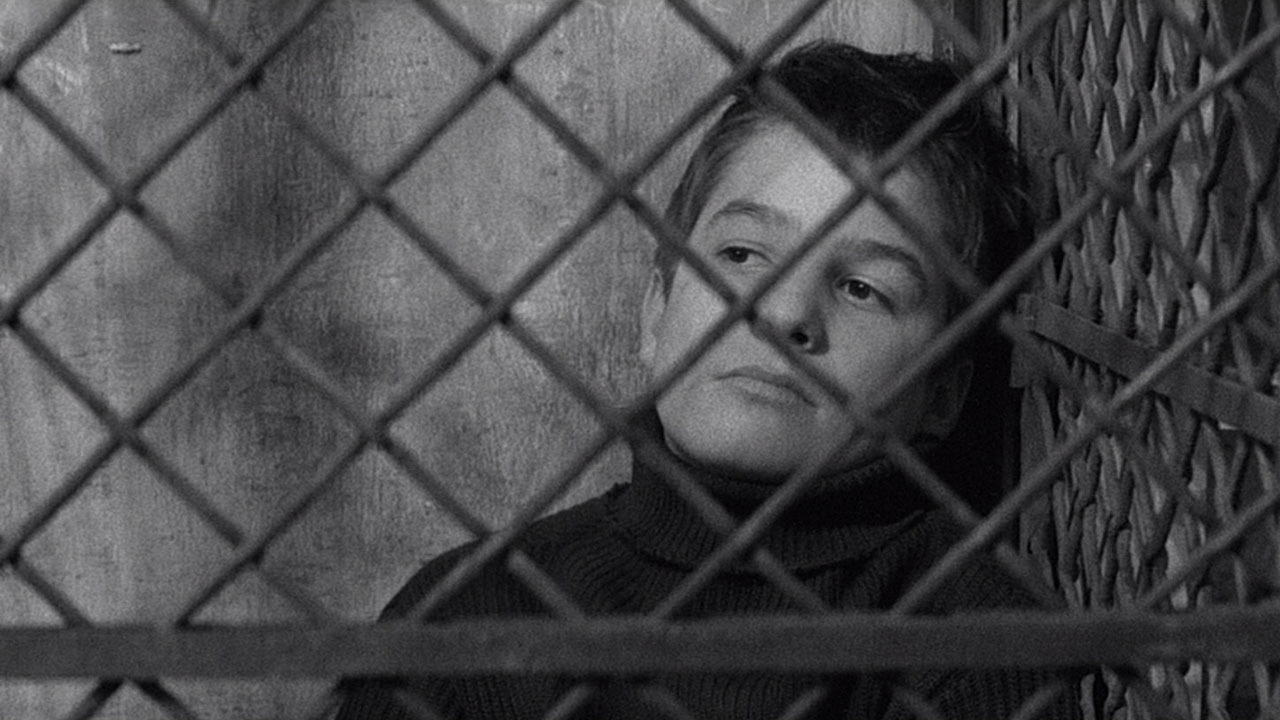

6. Les 400 coups (François Truffaut, 1959)

Probably the most familiar film on this list, Francois Truffaut’s 400 Blows is by many considered the definitive film about boyhood. It features a 14-year-old Jean-Pierre Leaud as Antoine Doinel. Leaud would become one of the most recognizable faces of the Nouvelle Vague. And Antoine too would later re-appear in a series of more light-hearted movies about the character (Stolen Kisses, Bed and Board, Love On The Run).

Antoine is an restless boy living in Paris. He intermittently skips school and runs away from home, to the dismay of his well-meaning parents and teacher. While the film is famous for its gut-punch of an ending, there is a lot of playfulness before the sombre conclusion. Truffaut has a lot of fun depicting the everyday life of Antoine – his affection for the character is obvious.

There are also plenty of nods to the power of cinema and literature. Antoine seems in his element when he’s sitting alone in a cinema, or engrossed in Balzac in his cramped bedroom.

7. Tirez sur le pianiste (François Truffaut, 1960)

Charles Aznavour, one of France’s most famous crooners, plays Charlie Kohler/Edouard Saroyan, a once-respected concert pianist going through a depression and biding his time playing in a dive bar. One of the waitresses gradually falls in love with Charlie, and both unexpectedly gets drawn into a criminal underworld when Charlie’s brothers fall foul of some gangsters.

Much less well-known than Truffaut’s 400 Blows and Jules et Jim, Shoot The Pianist is nevertheless a classic Truffaut movie, displaying all the cinematic fluency cinephiles have come to expect from the French master.

It’s based on a British crime novel by David Goodis. But Truffaut transferred the the action to Paris, and significantly changed the characters to make them less conventional. Where crime novels typically feature strong, confident men and weak or duplicitous women, Truffaut makes his protagonist vulnerable and introverted, and makes his women strong and independent.

Tirez Sur Le Pianiste is often seen as something of a collage, in that there are elements of multiple genres (and styles) at work. But at its heart, it’s a powerful character study. Truffaut’s technical accomplishments, while impressive as usual, never distract from the story that he’s telling.

8. A bout de souffle (Jean-Luc Godard, 1960)

Godard’s first feature-film, A bout de souffle (often translated as Breathless) is perhaps the most iconic movie of the Nouvelle Vague, thanks partly to the performance of Jean-Paul Belmondo, who would soon become one of the icons of French cinema. The title is a good indication of what to expect.

Belmondo plays Michel, a young criminal who steals a car and somewhat haphazardly shoots a policeman in Marseille. In Paris he seeks refuge with Patricia (played Jean Seberg), a young American student selling newspapers to get by.

Michel idolizes Humphrey Bogart. This facet of Michel gives the film an air of self-consciousness: at times it plays like a tribute to – or pastiche of – film noir. But Michel’s love of Bogart makes this aspect dramatically intriguing – is Michel trying to live inside his own film noir?

The film is typically Godardian in this sense – the boundary between reality and art is radically blurred. In terms of both form and content, Breathless is like a youthful – more wild and fleeting – film noir.

9. Bande à part (Jean-Luc Godard, 1964)

Along with Breathless, Bande à parte (sometimes translated as Band of Outsiders) is generally seen as Godard’s defining contribution to the early Nouvelle Vague. It is also considered his most accessible film. “A Godard film for people who don’t much care for Godard” as Amy Taubin put it.

Based on a pulp novel by Dolores Hitchens, it features many common elements of the crime caper genre, but a self-referential voice-over gives the film a different feel. The voice-over addresses the people who are sitting in the cinema, watching the movie.

The film is therefore aware of itself as a movie, and doesn’t pretend to be “realistic”. This gives Godard the freedom to be as playful as he wants. For example, there is a point at which the sound cuts off, when one of the characters asks for a minute’s silence.

It’s a film that has been referenced many times by generation after generation of film-makers. Most famously, Quentin Tarantino took inspiration from Bande a Part’s dance scene for his own iconic dance scene in Pulp Fiction.

10. Le boucher (Claude Chabrol, 1970)

In a small village in the Périgord region of France, two very different characters meet at a wedding. One is Hélène, a young and popular teacher, the other is Popaul, a somewhat coarse butcher. As their platonic friendship develops, news gradually emerges of a series of brutal murders of women in the area, and Hélène grows increasingly suspicious of Popaul.

Chabrol is often termed the French Hitchcock. Like the British director, he was a master of suspense. But there is a satirical bent to most of Chabrol’s films, bringing them above mere hommages to a better-known master.

Occasionally gentle, but mostly brutal, Chabrol picked apart the hypocrisies of the middle-classes. Le Boucher is also a critique of France’s colonial past and present. Connections are drawn between the killings in the French village and the French campaign in Algeria – a campaign Popaul has just returned from.

Like Luis Bunuel, Chabrol confronted polite surfaces with the barely hidden horrors beneath. But unlike Bunuel, Chabrol’s films are tightly plotted and linear – their political intentions are artfully woven into suspenseful thrillers, accessible to audiences totally unfamiliar with the ins-and-outs of French politics.

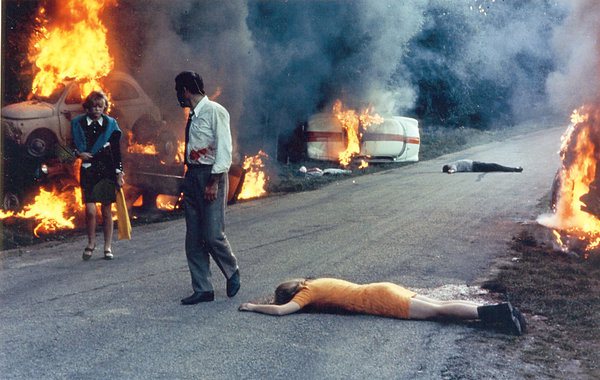

11. Weekend (Jean-Luc Godard, 1967)

While undoubtedly one of Godard’s more aggressive affronts to his audience, Weekend still has enough wit and energy to make it worth the effort. Featuring a cast familiar to fans of Godard’s more accessible films (Jean Yanne, Jean-Pierre Leaud), Weekend is something of a black comedy, depicting a weekend in hell. From the start, Godard uses various methods to distance his audience.

Perhaps the most jarring technique is when inappropriate music interrupts the dialogue, making the plot somewhat hard to follow. At its core, like so many films of the French New Wave, it’s a satire of middle-class hypocrisy.

Corinne and Roland are a married couple, both with secret lovers, and both with plans to kill the other off. They set off in their car to see if they can obtain an inheritance from Corinne’s dying father, but things rapidly get complicated.

The first problem is a massive traffic jam. This scene is perhaps one of Godard’s most famous coups-de-cinema – an eight-minute tracking shot of a long, long traffic disaster. And there are plenty more grisly traffic accidents to come throughout the movie.

After this scene, things become more and more picaresque and also political. Less entertaining than the traffic chaos, but just as audacious, is a five-minute segment where two garbage-men stare into the camera, eating sandwiches and delivering abstruse political monologues about class conflict.

Though it was made in 1967, Weekend seems to typify the spirit of 1968, especially given the later scenes in a commune of hippies who practice cannibalism and guerrilla warfare. The film is a document of intense political turmoil in France during the late 60’s – a conflict between social classes, certainly, but also a conflict between older and younger generations.

Godard is careful not to turn his film into an obvious manifesto for a particular form of action. His intention has always been to unsettle the viewer’s assumptions about art, of course, but everyday life. And – frustrating for a lot of viewers – he never provides any easy answers to the problems he poses.

Author Bio: Ciaran is originally from Dublin, Ireland, but currently lives in New York. He has passionate interest in European and Japanese cinema – the old stuff in particular. The directors who have left the deepest impression on him are Jacques Rivette, Eric Rohmer and Marco Ferreri.