5. Tomu Uchida (1898 – 1970)

Despite being hailed as one of the great masters of Japanese cinema, Tomu Uchida is an unfamiliar name to the Western world. His acclaimed release of the “Zen and Sword” series—a relatively conventional, expertly crafted six film account of the exploits of real-life swordsman, Musashi Miyamoto (1584 -1645)—acquired him his recent reputation (in the West) as a supplier of well-made jidai-geki (period films). Nevertheless, Uchida’s work demands wider exposure for its diversity and mastery of style.

Directing his first film in 1922, Uchida became known as directing keiko eiga (leftist “tendency” films), which examine the regressive structures of Japanese society. One of Uchida’s few extant— but most acclaimed—films of the prewar era is “Earth” (Tsuchi, 1939). This film is a startlingly realistic portrayal of the peasantry, which stylistically combines the pictorial qualities of classic Japanese cinema with a rhetorical style akin to Soviet montage and German expressionism.

During the war, this progressive and liberal director supposedly transformed into a right-wing militarist who willingly made propaganda films for his fascist country. This, and the assumption that he was a mere journeyman director of popular period spectacles in the postwar era, probably was the reason for his initial dismissal by the critics. Often overlooked, however, is that while he churned out successful period films, he also continued to direct numerous contemporary works with his trademark observant attitude.

One of his greatest masterpieces is also one of his last films: the crime drama, A Fugitive from the Past (Kiga Kaikyo, 1965). The film is nearly three hours long and deeply-rooted in the Buddhist Zen philosophy, and it includes themes of guilt, redemption, and the inability to escape one’s past. Moreover, A Fugitive from the Past ranks among the greatest works of Japanese cinema and reveals its director as a socially critical master whose re-exposure to the West is long overdue.

4. Tadashi Imai (1912 – 1991)

Having won the respected Kinema Junpo Award no less than eight times (the Japanese equivalent of 8 Academy Awards), Tadashi Imai is regarded, in Japan, as a towering figure in the pantheon of local film directors. In the 1950s and early 1960s, he also gained short-lived popularity in Europe.

Several of his works were screened in Cannes; his film, Story of Pure Love (Jun’ai monogatari, 1957), was awarded the Silver Berlin Bear at the 1958 Berlin International Film Festival; and his jidai-geki, Cruel Story of Bushido (Bushido zankoku monogatari, 1963), won the Golden Berlin Bear Award.

Despite these accolades, Tadashi Imai never gained notable attention in the U.S and is largely ignored by Western film scholars. This Western critical and scholarly neglect is probably because of his political ideologies. When the Cold War was at its peak, Tadashi Imai supported the Communist regime and dared to attack, in his films, the Japanese neo-feudal structures, as well the Western capitalistic society.

Imai made his first film during the war and initially started by directing kokusaku eiga (“national policy films”)—right-wing propaganda films, which were imposed on Japanese directors by the government to strengthen the war effort. Later, Imai called those films the biggest mistake of his life. Thus, after the Cold War, the supposedly right-wing propagandist turned into one of the harshest critics of the Japanese cinema.

Today, Tadashi Imai is mostly known for his numerous war films. The best of them, Tower of Lilies (Himeyuri no to, 1953), is about several combat nurses losing their lives on the battlefield. It was one of the most purely anti-war films the Japanese cinema had ever produced during this time period. Imai, however, was not limited to films about war.

Kiku and Isamu (Kiku to Isamu, 1959), for example, deals intelligently with the racism endured by a mixed-race offspring of a Japanese woman and an African-American soldier. A Story of Echigo (Echigo tsutsuishi oya shirazu, 1964) examines the suppression of a rural woman, who is raped by her husband’s co-worker, and she is subsequently killed by her husband because of her supposed “infidelity.”

Among his jidai-geki is Night Drum (Yoru no tsuzumi, 1958), which should be considered as one of the harshest indictments of Japanese feudalism. Narrated via non-linear flashbacks, the story is about a high-ranking samurai’s wife who is suspected of having committed adultery during her husband’s absence.

The film concludes with one of the most intense facial close-ups of all World cinema. The face is that of the husband who committed several horrible acts in accordance the Samurai feudal code. The husband subsequently realizes that he has destroyed his life by committing those allegedly honorable acts in order to avenge his wife’s unfaithfulness.

Though Japanese critics refer to Imai’s style as “nakanai realism” (realism without tears), Western critics often argue that the director’s melodramatic content often undermine the analysis of the social realities responsible for the tragedy of his characters. Yet, it is the melodramatic content that emits the impressive emotional resonance of his films, which supplies Imai’s work with a characteristic humanism and sincerity one seldom finds in ideologically motivated films.

3. Satsuo Yamamoto (1910 – 1983)

While Donald Richie spared Tadashi Imai from overly harsh criticism in his groundbreaking study on Japanese film, “The Japanese film: Arts and Industry” (1959), it was fellow communist Satsuo Yamamoto who endured the full amount of the prevalent anti-communist sentiment in 1950s America. Besides singling out the quality of a few of Yamamoto’s works, Richie accused the director of making political propaganda and called him a director who “uses an axe where he should use a scalpel.”

Since Donald Richie’s book still continues to be the only in-depth English-language discussion of Yamamoto’s films, it is not surprising that Yamamoto’s socially conscious and highly critical oeuvre is now largely neglected in the West. However, in recent years, he has gained some attention for his numerous period films he made when he was contracted as a director for the Daiei Studios.

The two films Yamamoto directed for the ninja series, Shinobi no mono (1962–1966), have been hailed by genre fans as being the first to escape the prevailing portrayal of the ninja as a superhuman warrior. Instead, Yamamoto realistically presents the ninjas as highly-skilled spies, who do not fight with wizardry, but with elaborate military tactics and clever deceit.

Initially, Yamamoto worked for newly founded P.C.L (later renamed Toho Company). In the late 1940s, when Japan was purged by the American occupation, Yamamoto was one of the first directors who worked independently from the big studios. While employed at small left-wing companies, he exclusively committed himself to directing shakai mono (“social-problem”) films, which examined the flaws of modern Japanese society.

The Sunless Street (Taiyo no nai machi, 1954), for example, chronicles the tale of a prolonged strike at a printing plant, and The Ivory Tower (Shiro Kyoto, 1966) criticizes Japanese medical ethics. One of Yamamoto’s most acclaimed films of this period is Vacuum Zone (Shinku Chitai, 1952). A harsh indictment of the violence and corruption in the Army, Donald Richie calls Vacuum Zone “the strongest anti-military film ever made in Japan.”

Yamamoto, who was popular with the critics and the public, directed these socio-critical films well into the 1980s. In the late 1970s, he filmed a follow-up to his earlier Nomugi Pass (Aa, Nomugi toge, 1979)—an account of the exploitation of silk farmers during the Meiji era. While many of his films were indeed deeply infused with communist ideology, the controversial themes of his works never felt forced or overly propagandistic.

At best, Satsuo Yamamoto’s films were tremendously powerful and deserve rediscovery for their bravery to expose the social issues of Japanese society by-passed in the West.

2. Shiro Toyoda (1905 – 1977)

Shiro Toyoda is another director completely misrepresented by the few films of his released on DVD in the West until now. The two pictures in question are Illusion of Blood (Yotsuya kaidan, 1965) and Portrait of Hell (Jigokuhen, 1969).

The former is a pedestrian adaption of the popular ghost tale (Kaidan eiga) “Yotsuya Kaidan”; the latter, though somewhat routine, is an expertly crafted adaptation of a short story by the famous author, Ryunosuke Akutagawa. Unfortunately, these films were made during a decline of the Japanese film industry; thus, they were weakened by commercial consideration and rushed production schedules.

Notwithstanding the relative conventionality of his later work, during his prime, Shiro Toyoda was considered a first-rate director who was famous for his numerous adaptions of high-brow literature. Making his debut as a director in 1929, Shiro Toyoda soon became associated with the junbungaku (pure literature) movement, which had the goal of translating and adapting the most prestigious works of Japanese literature into film.

While Shiro Toyoda was never interested in just creating cinematic copies of famous books, he always tried to capture the essence and tone of the piece he adapted. Thus, he managed, in Snow Country (Yukiguni, 1957), to reproduce the exact feeling of loneliness and purity of Nobel Prize winner Yasunari Kawabata’s novel of the same name.

A Cat, Shozo and Two Women (Neko to Shozo to futari no onna, 1956) is another adaptation about a man and his unhappy relationship with his first and second wives. This film is celebrated in Japan for his witty and delightful humor, and its release in the West would serve as the perfect introduction to the classic Japanese comedy. A classic genre, which, like director Shiro Toyoda, is still largely uncovered by Western critics.

Similar to Kozaburo Yoshimura, Shiro Toyoda never developed a personal style and changed the tone and setting of each film to fit its source material. However, it could be argued that he united his work with his constant desire for carefully developed characters and intelligently constructed stories and visual imagination. Unfortunately, the discount of his achievements, based only on his later works, is truly unjustified and misguided.

1. Kozaburo Yoshimura (1911 – 2000)

Kozaburo Yoshimura is one of those directors whose diversity actually hindered his breakthrough in the West. In Europe and America, Yoshimura is practically unknown, despite the fact that he made some of the most innovative films of Japanese cinema. Furthermore, the eminent authority on Japanese film, Donald Richie, named the director as one of the seven greatest Japanese directors. Moreover, Yoshimura founded the production company, Kindai Eiga Kyokai, with famous director Kaneto Shindo.

The collaboration resulted in a productive relationship—Kaneto Shindo wrote the screenplays for Yoshimura’s films—and the duo produced some of the most fascinating and diverse films of Japanese cinema.

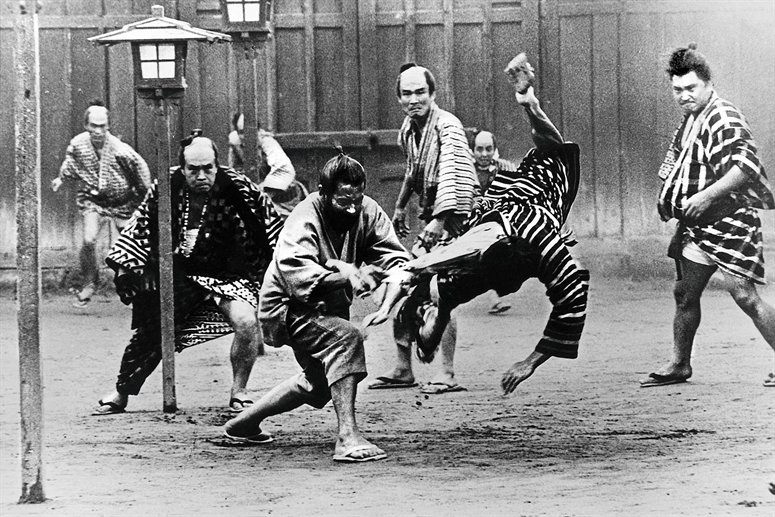

Their film, Ishimatsu of the Forrest (Mori no ishimatsu, 1948), is hailed as one of the first jidai-geki to level harsh criticism against modernity, despite the film taking place in the past. Very different and even more acclaimed is The Ball at the Anjo House (Anjo-ke no butokai, 1947). Through its melodrama of an aristocratic family who is forced to sell their house, the film examines the changing of the old class system in postwar Japan and surprisingly concludes with one of the most beautiful scenes of Tango dancing in World cinema.

In films like Clothes of Deception (Itsuwareru seiso, 1951) and Sister of Nishijin (Nishijin no shimai, 1952), Yoshimura addresses the issues of independent women in the postwar era. In those films, Yoshimura shows that although a massive technological innovation transpired, social prejudices, unfortunately, remained intact in the post-war era. His sequence of films about women, often employed as geisha in postwar Kyoto, acquired recognition for Yoshimura as a worthy successor of Kenji Mizoguchi—the legendary director who had died in 1956.

From the time he made his debut in 1934 until he directed his last film in 1974, Yoshimura never bothered to cultivate a uniting style in his body of work; he tried, however, to construct his style to fit the content of each film.

Thus, A Tale of Genji (Genji monogatari, 1951) almost reached the old master’s visual elegance and pictorial beauty—despite the film being even more melodramatic than any of Mizoguchi’s films. The Beauty and the Dragon (Kabuki juhachiban: Narukami: Bijo to kairyu, 1955), on the other hand, is considered by many as one of the only works to successfully combine the stylistic devices of kabuki and film.

Notwithstanding the widespread desire for directorial unity of Western critics, it was in fact exactly this diversity of content and style in Yoshimura’s films which made so many of them classics. In a Yoshimura film, every curious viewer will find one of the most innovative masters of Japanese cinema. The director’s expertise and intelligence made even his minor works truly exceptional pictures.

Author Bio: Pablo is a 20-year-old freelance critic and film historian from Germany. He is fascinated by classical Japanese cinema of the 20th century, you can check out his website at http://www.nippon-kino.net/.