7. The Arbor (Clio Barnard, 2010)

The concept behind The Arbor sounds like a fine art student’s thesis video project, which escalated beyond belief. However, it presents an interesting way film can form a portrait of a person, without ever seeing them directly.

Borrowing several techniques from Documentary theatre (Verbatim theatre), where actual word-for-word testimonies are performed by actors on a stage. The film pushes this method slightly further, using audio recordings of people who knew the British author Andrea Dunbar and having actors lip-sync to them.

Andrea Dunbar is remembered primarily for her stage play Rita, Sue and Bob Too,which was adapted into a film by Alan Clarke in 1987.

8. Medium Cool (Haskell Wexler, 1969)

Directed by Haskell Wexler in 1969 and like a lot of films that play with documentary and fiction, Medium Cool is branded a ‘meta’ film. A movie is referred to as ‘meta’ (meta-texual) or ‘metafiction’,when it references itself outside of the film’s world.In Medium Cool’s case, despite it mixing elements of documentary and fiction, it frequently draws the audience’s attention back to the fact they are watching a film.

These techniques are usually used to challenge certain conventions of film,and alter the way audiences digest a story by entitling them to additional ‘inside’ information.

Medium Cool follows a TV reporter who encounters the violent outbursts surrounding the 1968 Democratic National Convention and how he begins to develop a personal involvement with it.The film’s aesthetic and historical significance is regarded so highly, that the US National Film Registry selected it for preservation in 2003. The film also ponders over the ethical and journalistic responsibilities a documentarian encounters when shooting footage.

9. London (Patrick Keiller, 1994)

In 1994, British filmmaker Patrick Keiller introduced his idiosyncratic documentary style to the world with London. The film is a text book example of how powerful hard-core subjective documentary filmmaking can be, and the poetic correlation between people and place.

Using a fictional protagonist who narrates his thoughts and various stationary shots of the city; the film produces a pessimistic, yet charming commentary about London during one of its lowest points in modern times.

‘London’ is a personal portrait of a city,a record of a significant year for England’s capital and a testimony to the existential effects an environment can have on its people.

10.The Night It Rained (Kamran Shirdel, 1967)

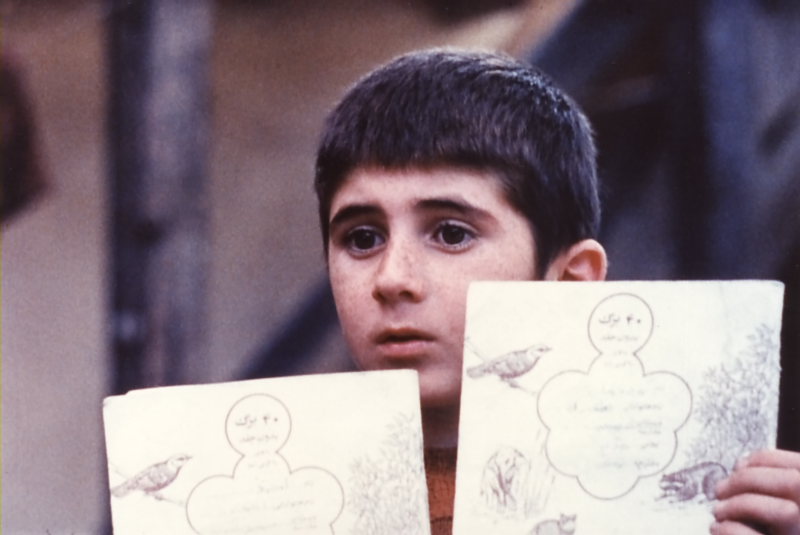

Iranian filmmaker Kamran Shirdel’s 35 minute film is to documentary what Kurosawa’s Rashomon is to narrative.The film is made up of several contradictory testimonies, all claiming to either support or reject the notion that a young boy single-handedly prevented a train crash.

Set in northern Iran, The night it rained focuses on a schoolboy from a small village who allegedly saw a train approaching flooded rail tracks. In an act of bravery he set fire to his jacket, ran towards the train and averted a serious and fatal accident.

The film interviews; railway employees, governors, police chiefs, teacher and pupils, all to which tell a different version of the event. It creates a poignant image of the Iranian society; where reality and fabrication can no longer be differentiated.

11. F for Fake (Orson Welles, 1973)

F For Fake was directed by Orson Welles in 1973 and was his last complete feature film.Hosted and narrated by Welles himself, the film explores several reasons why filmmaking (and art in general) is innately deceptive. The film opens with Welles performing sleight-of-hand magic tricks for some children and woman from a train asks him “Still up to your old tricks I see?”. Welles replies “Why not? I’m a charlatan!”.

He then goes on to say to the camera, “Almost any story, is almost certainly some kind of lie … but not this time, this is a promise. Everything you hear from us is true and based on solid facts”.

Of course Welles lies to us, because the whole film continuously attempts to trick the audience and obscures what is true and fictitious.However, it’s really our own fault for falling for it; Orson had already warned us from the beginning that he is a charlatan.

The whole movie is pretty much a bag of tricks and Welles uses them to highlight parallels between fakery and art. Ironically it uncovers a type of truth that could only be revealed through lies.

12. Abbas Kiarostami’s Koker Trilogy (1987, 1992, 1994)

Even in his more conventional narrative films, Iranian director Abbas Kiarostami has a reputation for obscuring what is real and contrived.So much in fact, I could have pretty much named any movie from his filmography and it would have applied to the list in some way.

Despite Kiarostami himself rejecting the idea that Where Is the Friend’s Home? (1987), Life and Nothing More (1992) and Through the Olive Trees (1994)even make up a trilogy, it’s hard to ignore their meta textual associations.

The plot of each movie concerns itself with the production of the film that preceded it.Life and Nothing More was about the filmmaker (fictional version of Kiarostami) who directed Where Is the Friend’s Home?and his struggle attempting to find the boy who played the leading role.Through the Olive Trees is based on the production of Life and Nothing More and depicts the subtle between the actors taking part in the film.

In typical Kiarostami fashion, although the individual films are minimalist and focus more on small moments rather than cohesive stories, as a trilogy they are both thematically and intertextually complex.

13. In Vanda’s Room (Pedro Costa, 2000)

Again, Pedro Costa is one of those filmmakers that made a habit out of dabbling with the lines that separate reality and narrative.In Vanda’s Room proved to be a major turning point in Costa’s career, it was the first time he attempted to implement methods from both documentary and dramatic narrative.

The film follows the everyday life of a woman called Vanda Duarte, a drug addict living in the slums of outer Lisbon. The film uses long static compositions; all shot on a DV camera, by a filming crew that often consisted solely of Costa himself.

As a result of the film’s minimal, yet profound narrative efforts; it is almost too easy to assume everything in the film is actuality. The weighty and illusive sense of naturalism, combined with the stunning Bressonian cinematography, produces a beautifully hypnotic portrait of a world riddled with malice.

In Vanda’s Room has the aesthetics of a Straub-Huillet drama and the quiet probing nature of a Fredrick Wiseman documentary.