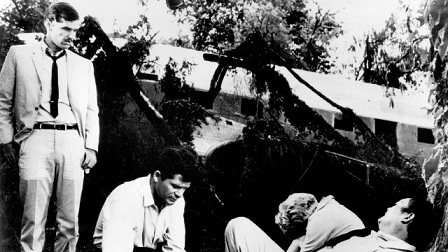

6. Flight to Fury (1964, Monte Hellman)

An early Jack Nicholson thriller directed by the future executive producer of Reservoir Dogs, Flight to Fury is about an expedition of treasure hunters in the Philippines. It’s a classic arrangement of unlikely comrades pitted against the forces of nature. There is a plane crash, and the two men who survive find themselves lost in the jungle. One of the men is a homicidal fortune-hunter. The other is an international adventurer. They push and pull at one another over differing desires and personalities while trying to survive in the steamy wilderness.

Monte Hellman moved on from the Roger Corman Film School to become an underground filmmaker, part of the counterculture of the 70s. A film he made that is now considered his masterpiece, Two-Lane Blacktop, was such a flop that it stalled out his career. Until he met the unknown Quentin Tarantino who was hawking a script entitled Reservoir Dogs, the man characterized by Sam Peckinpah on national television in 1973 as “the best director working in America today” could not get a film made.

At first he tried to convince Tarantino to let him direct Reservoir Dogs, but Tarantino insisted that it was to be his debut. So, Monte Hellman said that he’ll be the executive producer.

7. The Taking of Pelham One Two Three (1974, Joseph Sargent)

This is where the color-coded nicknames came from. Mr. Blue is in charge. Mr. Green has a cold. Mr. Grey is violently unstable. Mr. Brown is easily dispatched. Tarantino added Mr. Blonde and made him the psychopath, Mr. White becomes the heist leader, Mr. Pink who survives the heist and confrontation at the warehouse, and Mr. Orange who is the undercover cop.

The Taking of Pelham One Two Three is a hostage thriller set in the subway of New York City. Disguised hijackers board a subway car, detach it from the rest and demand a million dollars in exchange for the lives of their hostages. Tensions rise and destroy the criminals’ unity. There is a whodunit element to the police side of the plot. A Transit Authority Lieutenant tries to identify the hijackers, leading to a final scene of revelation.

The film was a big success and to this day New York City dispatchers avoid having trains at Pelham station leave at 1:23. Tarantino’s use of the color-coded nicknames differs from the whodunit plot of The Taking of Pelham One Two Three in that it is the criminals themselves who are concealed from one another. The police have no factor in uncovering identities or discovering who these thieves are. It is the audience of Reservoir Dogs who learn their backstories through flashback. And since the thieves often only know one another by their code names, it feeds their paranoia, leading to the final stand-off.

8. The Big Combo (1955, Joseph Lewis)

Perhaps the scene that made Tarantino’s name is when Mr. Blonde tortures a cop with a razor blade and nearly sets him on fire. This was also a centerpiece in The Big Combo. The staging of torture and interrogation in films is often limited to the dramatic. Chairs set in stark light, only a few interrogators and one victim. Predictable dialog. The sly addition made by The Big Combo was music. By having the torturers play music while they beat their victim adds an aesthetic layer to the scene, transgressing our sense of seriousness around torture.

In Reservoir Dogs, this is much more ironic. Stealer’s Wheel is poppy, upbeat, Dylanesque in the cool sense. The Big Combo is more sympathetic to the dramatic circumstances, as the gangster Mr. Brown and his thugs torture Lt. Leonard Diamond, who is trying to find out what happened to a woman in Brown’s influence who disappeared. He is also in love with Brown’s girlfriend. The Big Combo plays out the film noir tropes of obsession and betrayal better than most of the latter-day examples of the genre. A key appropriation is the foggy airplane hanger, already iconic from Casablanca, where the final shoot out occurs.

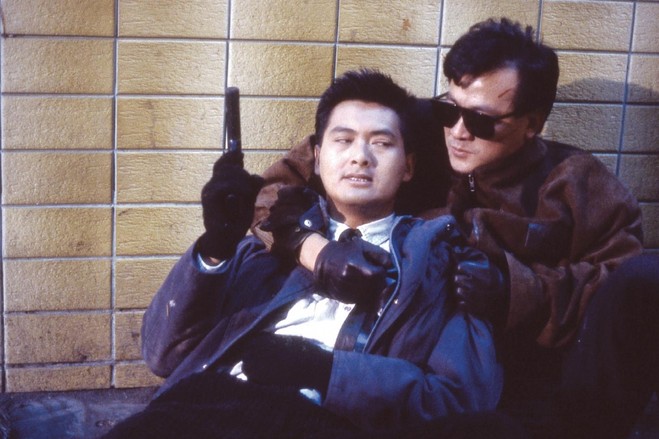

9. A Better Tomorrow 2 (1987, John Woo)

John Woo’s sequel is even more violent, melodramatic, and gory than the first installment, which was very violent, melodramatic and gory. In the world of 80s action movies, John Woo was the light of hope amid darkness to Quentin Tarantino. He orchestrated shoot outs like no other, sending bodies flying in all the clichés that we now take for granted. The black-and-white morality of the setup throws everything into making the bad guys terrible and the good guys powerful. And the black suits and ties with white shirts became a sartorial distinction in Reservoir Dogs, much copied throughout the 90s by Ska bands and Indie filmmakers.

Chow Yun Fat, who plays the twin brother who emigrated to America, stalks the streets of New York City in a tan coat, aviator sunglasses, and a match between his lips. In a moment of pure fandom, Quentin Tarantino copied this look, walking around Los Angeles dressed like Chow Yun Fat for three months. Since that time, the actor he once thought of as a Chinese Alan Delon no longer holds his fascination.

Although the tropes of A Better Tomorrow 2 might be comical to contemporary audiences, Tarantino maintains that Hong Kong cinema was more invigorating than any other at the time and he remains a champion of its directors and actors today.

10. City on Fire (1987, Ringo Lam)

Another Chow Yun Fat crime flick, this time following the exact plot turns of Tarantino’s debut Reservoir Dogs. Again the criminals are jewel thieves. Again they botch the job when an alarm is set off and they are instantly surrounded by cops. A few get away and sniff out an undercover cop in their ranks who is defended by a friend leading to a Mexican Standoff where everyone dies. The policeman and his defender live just long enough for the policeman to come clean to his friend.

What makes this entirely forgettable action film interesting in terms of Quentin Tarantino’s development is the parts that are different. For example, Tarantino does not show the actual robbery. At first this was a budgetary decision but after the budget inflated, he chose to stick with it in order to focus the film on the suspicion and betrayal that follows the heist.

Atmospheric elements also suggest a very different kind of imagination behind the lens. Because it is all set in a day, Tarantino imagined time being marked by a radio special. “The Super Sounds of the Seventies” gives entrance to the music he wants to pair with his story, and indicates that there is a larger world outside the warehouse where the majority of the story unfolds.

Making excuses for the translation, dialog is still a key difference. City on Fire is expository or demonstrative of a character’s movement through the plot. The characters are beneath the plot in importance. Not so for Tarantino. The jewel thieves with their color coded names are both concealed and revealed as they chatter at a diner and try to piece together the fallout of their heist. The dialog is unambiguously Tarantino doing what many have imitated, poorly most of the time.

Following any list that Tarantino has made himself is an exercise in futility at best, falling for a ruse at worse. He’s a compulsive list-maker and his lists rarely have any overlap. Additionally, there is a difference between a film that a director calls his favorite and a film from which a director draws influence. Very often, directors are more impressed by films they could never make, nor would want to, than they are by the entries within their own stream of production. Tarantino’s stream of production is a mighty river of film history and pop culture detritus. It flows wide, and, in some key films, it flows deep as well.

Author Bio: Chris is a 29 year old grant-writer for a meditation retreat center in the Colorado Rockies, but he came here first to make short videos about the center. His favorite directors are Federico Fellini, Kurosawa, Billy Wilder, the Coen Bros., Stanley Kubrick, and Edgar Wright.